By: Andrés Gómez

Land dispossession, violence, and ecocide have marked the history of the Sikuani people since 1940. Armed clashes, forced displacement, and massacres carried out by the army, guerrillas, and settlers paved the way for control of their ancestral territories. But it was under the shadow of emerald miner war lord and paramilitary Víctor Carranza that thousands of hectares were finally seized.

Aliar-Fazenda, Colombia’s leading pork producer, and Mennonite religious groups dedicated to the mechanized cultivation of genetically modified soybeans and corn for pork industry, are consolidating the paramilitary dispossession, devastating the ecosystems of Puerto Gaitán and deepening a silent genocide that, for almost a century has threatened the physical and cultural survival of the Sikuani, as well as their roots in the land based on the mangoes and yopo they have planted and the companies are destroying.

The exile of the Sikuani

Amid the violence that consumed Colombia between 1949 and 1954, the liberal guerrillas of the Llanos clashed with the army, causing the displacement of indigenous peoples, especially the Sikuani. The indigenous people did not flee solely because of the fighting. Social control and the appropriation of their lands played an important role in their exile, as Sikuani leader Marcelino Sossa told the Truth Commission (CEV):

Dumar Aljure, it was said, was a guerrilla who had to defend the less fortunate peoples, but that was not the case. He did not allow our government, our culture, our way of life to function properly, because we lived in fear, we ran from one place to another; so much so that anyone who did not obey him, he killed. He put himself at the service of the rich of the time.

After Rojas Pinilla’s amnesty in the late 1950s, the Sikuani returned to the savannas and gallery forests that are their home in Puerto Gaitán, but they were unable to enjoy the waters and fish of the rivers and moricheras [wetlands], or hunting in the savannas, even less so the shade of the mango trees they plant to establish their permanent sites, nor the medicinal properties of the yopo tree that heals the spirit and body, trees that they have planted throughout the savanna for hundreds of years and that bear witness to where they have lived and where they have buried their loved ones.

Considering indigenous territories to be uncultivated, in the 1960s the state authorized the Meta I Project and invited evicted settlers to occupy the land.

Farmers and settlers who were already settled in the area harassed the Sikuani and pressured them to abandon their lands so that they could occupy them, to the point that in 1967, workers from the La Rubiela estate murdered approximately 40 Sikuani people, crimes that the State endorsed when it declared those responsible innocent in 1972: “According to Judge Carlos Gutiérrez, ‘the ignorance of the settlers and fear of indigenous fury were the main motivations for the murders.’”

The La Rubiela massacre was followed by the Planas massacre. In 1970, the army, together with the Administrative Department of Security (DAS), murdered what they claimed was a Sikuani guerrilla front allegedly led by Rafael Jaramillo Ulloa, but there were mining interests involved, as Rosalba Jiménez, leader of the Sikuani people, recalls:

There was also a specific interest in clearing the territory of Indians: oil deposits.

Under the pretext of arresting Jaramillo Ulloa, “Las Jaramilladas” began: massacres over territory, justified by the racism of the settlers towards the ancient peoples of the Orinoquía. Alexander Álvarez, a Sikuani leader, recalls that this ethnic cleansing meant that the people displaced from their village did not return:

Families fled to Venezuela, Guaviare, and Casanare, leaving only the territory behind. Those who left for Venezuela did not return, nor did those who went to Casanare…

Alba Rubiela Gaitán, governor of Barrulia, sadly recalls how four generations have fought against dispossession and racism:

My great-grandfather Ramón Gaitán, my grandfather Santiago Gaitán, and my father Ángel María Gaitán experienced the violence of Guadalupe Salcedo, as well as the violence of the jaramilladas. Then the paramilitaries dispossessed them […] My father did not sell any land, my father did not exchange any land, as some third parties claim.

After “Las Jaramilladas,” towards the end of the 1970s, and as they always did when the violence against them subsided, the Sikuani people returned to Puerto Gaitán, but they did not count on the arrival of the emerald miner, landowner, and paramilitary Víctor Carranza, who had organized a private army in the region since 1985: “Los Carranceros.” Alexander Álvarez recalls this when he and his family tried to return:

There were armed people at every gate. And they also had a chain across the road to prevent cars or anything else from passing. […] As I said, it used to be a public road, so if they were going to San Pedro de Arimena, of course, they would lift the chain and let motorcycles pass. But for anyone who suddenly wanted to come back or return here, they wouldn’t let them pass.

Carranza consolidates the dispossession

Alexander Álvarez’s words reveal the speed with which Carranza took over Puerto Gaitán and the frustrated attempts of the Sikuani people to return to their territories between Meta and Vichada due to the presence of armed individuals. And this paramilitary presence was not insignificant. Carranza’s command base was set up in Puerto Gaitán on the El Brasil farm, and served as a training school and a scene of torture and murder. This was stated by the Superior Court of Bogotá:

This farm was used to store food; as a dispensary; a mechanical workshop; a communications center; as well as a place of torture and imprisonment for people considered suspicious by the organization. […] It was the site of murders of members of the Meta and Vichada Self-Defense Forces, as well as of people considered enemies by that organization. From 1998 onwards, it was used as a ‘military preparation and training school’ according to the versions of the same postulates. This school was important for the organization as it had several military training areas along the Muco River.

The various episodes of violence prevented the Sikuani from moving freely in Puerto Gaitán. However, some members of the community would gather at certain times to travel through the land, go to the streams, and visit their ancestors. Governor Alba Gaitán recalls:

In the 1980s and 1990s, my father, along with other members of the community, including the traditional doctor who is the sabedor, traveled along the Muco River to various territories, including the communities of La Palmita, Chaparral, Mata Negra, La Pradera, and Los Cocuyos, but with the paramilitary violence, they were unable to return.

Despite the Sikuani’s insistence on returning to their lands, Carranza consolidated one million hectares in Meta: from the municipality of Puerto López, through Puerto Gaitán, to the department of Vichada. The paramilitary deepened the colonizing exile that had pushed the Sikuani decades ago to leave their territory, and this was continued by all the paramilitary groups that have controlled the region: the Autodefensas Campesinas del Meta y del Vichada (ACMV), the Bloque Centauros, the Ejército Revolucionario Popular Antisubversivo de Colombia, and, most recently, the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC) or Clan del Golfo. These groups have prevented the implementation of Decree 4633 of 2011, which recognizes the fundamental right to territory. Alexander Álvarez recounts:

And then a decree was issued saying that indigenous people had the right to reclaim their ancestral territories. So, I tried to enter, I applied again, I made a claim and everything. They didn’t give me permission to enter, but I went in anyway. I have been evicted five times.

Meta and Puerto Gaitán were home to the Sikuanis, Piapoco, and Sáliba peoples a little over 100 years ago. Today, only 30% of Puerto Gaitán’s population is Indigenous, mostly Sikuani, while control of the municipality lies in the hands of the Mennonite association Liviney that grows soy and corn, and the mega pork company Aliar-Fazenda, which have flattened and mechanized the land, destroying gallery forests, morichales, wetlands, streams, and rivers while consolidating the dispossession of the indigenous peoples.

From school of terror to pork factory

The land consolidation carried out by Víctor Carranza allowed Aliar-Fazenda to easily purchase thousands of hectares. One example is El Brasil, a 16,000-hectare farm that María Blanca Carranza, the paramilitary’s first cousin and wife, sold to the Aliar-Fazenda company, which used the land to start the business. The farm, which is now dedicated to agricultural production, served in the 1990s as a paramilitary base for Los Carranceros and the Autodefensas Campesinas de Meta y Vichada, as well as a hideout in July 1997 for the paramilitaries of the Bloque Centauros who committed the Mapiripán massacre.

This was also made possible by state support, which favored the demobilization of paramilitaries to allow for their rapid reorganization with political backing. During the administration of Álvaro Uribe Vélez, on June 24, 2008, President Álvaro Uribe showed his support by attending the plant’s inauguration:

I think the Agro Ingreso Seguro Law is a very good step, that the tax incentives are… I hope that here they can turn these large projects into free trade zones… which allows them to bring in all that machinery without tariffs or VAT. And it imposes a tax rate of only 15 percent, not 33, which will be the ordinary rate in Colombia.

During Juan Manuel Santos’s presidency, he did not travel to Meta, but the entire government leadership mobilized to Puerto Gaitán in 2015 to accompany the partners in laying the first stone of the slaughterhouse that would begin operating that year, with an investment of 30 billion pesos. Vice President Germán Vargas Lleras, then-Minister of the Presidency Néstor Humberto Martínez, and four other ministers were present, as well as a high-level delegation from Ecuador.

Presidential support backed the construction of the cold storage facility, which was completed that same year and built on land claimed in restitution by the Wacoyo Reservation, after La Fazenda leased 1,000 hectares of indigenous territory and presented that contract as alleged compensation for the damage caused to the community: In 2013, the company used biofertilizers made from pig manure, which caused skin and intestinal diseases and strong odors in the reserve, to the point that the community reported that ten children under the age of one died as a result of Aliar-Fazenda’s mishandling of 880,000 pigs’ daily manure. No governmental action was taken at the time.

Former president Iván Duque did not visit Aliar-Fazenda either, but in 2022 the National Land Agency (ANT) withdrew the protective measure for the Sikuani community of Barrulia, while denying the appeal filed by the indigenous people. Although the community subsequently obtained a favorable ruling, the revocation of that denial has not yet been resolved as it is a process with oppositions, all led by: La Fazenda, the Santa Clara Condominium Trust: representative of the El Brasil property, and the company La Isla y El Rosario S.A.

Apart from the legal dispute and territorial dispossession, Aliar-Fazenda’s imposition on indigenous lands is also reflected in the daily lives of those who work on their properties. The structural violence manifested in the expropriation also carries over into the company, where precarious working conditions directly impact members of the Sikuani community. Santiago, an indigenous Sikuani from the Wacoyo reserve, who asked that his real identity be protected for security reasons, explains:

You have to work Saturdays and Sundays… to get a day off, you have to work, you can’t miss a single Sunday, because they say you have to work on Sundays to get some compensation someday, when suddenly a family member gets sick, or you have to run an errand in town, well, something like that.

Raúl, another former worker, who also asked to keep his true identity confidential and who does not know Santiago, confirms his words and also denounces labor abuse, lack of medical care, and theft of work days:

It made us itch, it really did, like our bodies were burning. I mean, you get itchy all over […] A doctor’s appointment? Well, the truth is that they don’t treat you here, and if you miss work or don’t provide proof, they take away, let’s say, two days’ pay. Even if you bring them the proof later, they’ve already taken it away.

The El Brasil farm, and other lands seized from the Sikuani, function as pork factories and spaces of labor exploitation, but also as symbols of the systematic dispossession and impunity that has accompanied the expansion of Aliar-Fazenda. The company operates with state backing on indigenous territory and amid allegations of pollution, infant mortality, and labor abuse. However, it is not the only company devastating life in the Orinoquía region. Along with Aliar-Fazenda which is devouring life in Meta, the Mennonites are contributing to the genocide of the Sikuani people and the ecocide that Puerto Gaitán is experiencing today.

From paramilitarism to the Mennonite plow

The Mennonites are a religious group of the Anabaptist branch that emerged in the 16th century and was founded on pacifist principles, simple living, and autonomy from the state and official churches. Five hundred years later, some of the branches that have spread throughout Mexico, Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia have a different practice, colonizing with violence and becoming drivers of deforestation and a threat to biodiversity wherever they go.

In Mexico, Mennonite communities cleared 2,600 of forest without permits in the states of Yucatán, Campeche, and Quintana Roo, and set fire to the forest to convert the Mayan jungle into monocultures of soybeans, corn, and sorghum. In Bolivia, they were found guilty of drugging and raping 151 women and girls over a period of years, and in Peru, in regions such as Ucayali and Loreto, they have deforested more than 7,000 hectares between 2017 and 2023 to open up agricultural fields despite not having valid titles, destroying thousands of hectares of Amazonian forest and occupying the lands of the Shipibo-Konibo indigenous people with heavy machinery and the endorsement of regional authorities.

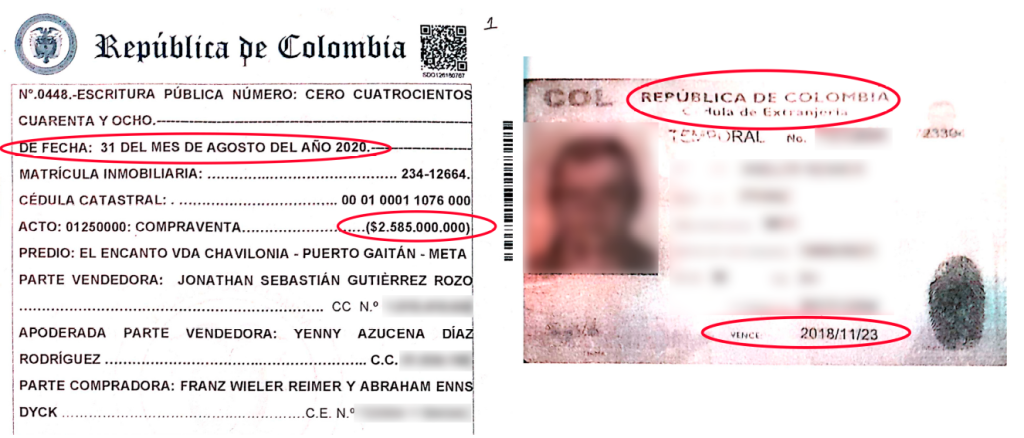

In Colombia, the Mennonites also contribute to the ecocide and indigenous genocide that their fellow congregants are carrying out in Central and South America. They currently own thousands of hectares of land in Puerto Gaitán, which they have accumulated by purchasing land, sometimes with expired identity cards, which would make the purchases of these plots illegal.

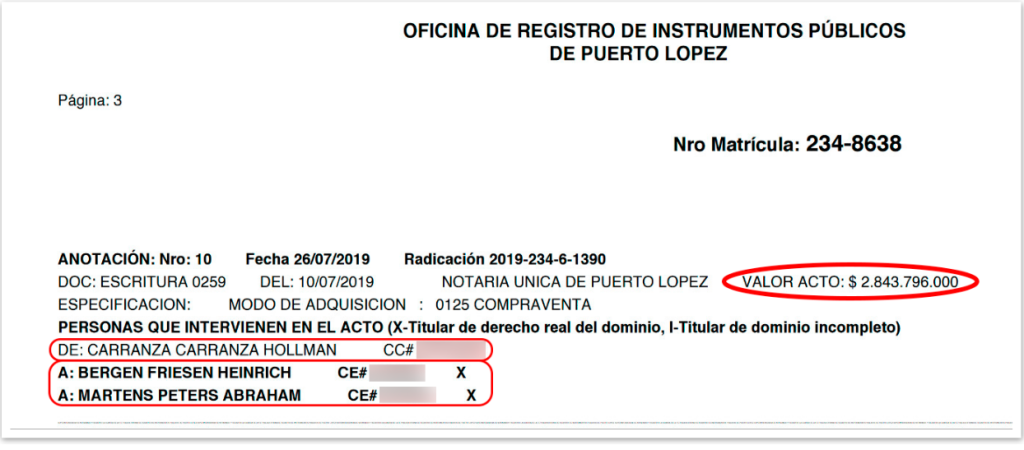

On other occasions, and like Aliar-Fazenda, the Mennonites have acquired land from the heirs of Víctor Carranza. Hollman Carranza Carranza, son of the feared paramilitary leader, sold land for almost 3 billion pesos to Bergen Friesen Heinrich and Martens Peter Abraham:

The heirs and close associates of Víctor Carranza benefited from the paramilitary dispossession and accumulated vacant land, and then favored the hoarding of the Mennonites, who, through apparently legal procedures, have accumulated almost 30,000 hectares, thus continuing the process of dispossession of the Sikuani people.

In 2013, these people who are now farming there were not there yet; they did not exist at that time, and they evicted me. I returned two years later, in 2015, and built my house, cleared a small plot of land, planted food, and everything. After a month, another eviction. That was the year the Mennonites arrived. They were already plowing there. When they saw that I had returned, that I had come here to settle down, they [Franci Bolaños, Jaime Ballestero, and Karina Barragán] knew that this belonged to the indigenous people, so they tried to sell it. So, in order for them to sell it, they evicted me.

Alexander Álvarez’s words reveal that he was evicted before the Mennonites arrived, but they also highlight that once the religious group arrived, those who sold them the land have been involved in the dispossession, a situation observed by Wilson Arias, a senator who has exercised political control over the actions of the Mennonites in Puerto Gaitán:

We have found a series of names close to some families that Carranza had left there and who are the ones selling to them. And they are sometimes the ones who hire the lawyers who are there in the eviction processes. In other words, the Mennonites use those who sold to them, basically so that they are the ones in charge of the eviction.

Wilson Arias’ words reveal that those who sold the Mennonites land taken from the Sikuani may be the key link between paramilitarism and the eviction processes. This is consistent with the situation of judicial harassment and threats to life experienced by the Sikuani, and in particular by one of their leaders, Alexander Álvarez:

Franci Bolaños, Jaime Ballestero, and Karina Barragán. These are three people who always pay or order our eviction. It was in 2015, and it happened again in 2017 […] Well, I am threatened by the same people who say they have been watching here for years. They think and believe or say that it is not indigenous territory, but that I am invading it. So, the Mennonites put some armed people in place to kill me, but they haven’t found me that easily yet.

Alexander Álvarez’s caution is not unfounded. On July 13, 2025, William Gaitán, health advisor to the Sikuani Asounuma indigenous organization and manager of the Matsuludani indigenous IPS, was murdered.

Wilson Arias also claims that the religious group intimidates the Sikuani people who are defending their right to return to their territories:

The Sikuani are surrounded by the Mennonites, who also use unholy forms of domination and, let’s say, lordship over the land. They use private security companies that are often seen and even hooded. Eh, it’s notoriety eh their armament of knives, of short-range weapons sometimes.

El Turbión is witness to the fact that Mennonite security personnel control interdepartmental roads such as the one from Puerto Gaitán to San Pedro de Arimena, which is reminiscent of the practice established by Carranza of controlling the passage of all people on the region’s roads.

Aliar-Fazenda and the Mennonites are not only accumulating hectares, but also reproducing a historical pattern of violence, displacement, and ecocide that threatens the physical and cultural survival of the Sikuani. The memory of the massacres, evictions, and threats remains alive in a desert of soybeans and corn, and in the frustration of not being able to enjoy the waters of the morichales, the sweetness of the mango and the shade of its tree, or to visit their ancestors, which reminds us that the effective restitution of territory is not just an administrative act, but a small action to stop a silent genocide that is still taking place in the savannas of Meta.

* This story is part of an investigation by El Turbión, carried out with the support of Global Exchange and Brighter Green’s Animals and Biodiversity Reporting Fund, and is part of a series that documents how violence, land concentration, and ecocide threaten the physical and cultural survival of the Sikuani people.

In recognition of El Turbión’s commitment to integrity and excellence in journalism, the outlet has obtained the Certification of the Journalism Trust Initiative, promoted by Reporters Without Borders under the international standard CEN CWA 17493:2019.

Si encuentras un error, selecciónalo y presiona Shift + Enter o Haz clic aquí. para informarnos.