Research: Joanna Zapata, Marcela Zuluaga, and Omar Vera

Audiovisuals: Iván Castaño

Drone footage: Plinio Barraza

The environmental footprint that Glencore has left in northern Colombia is evident. Vast expanses of tropical forests in the departments of Cesar and La Guajira, where the Swiss company operates open-pit coal mines, have accumulated four decades of deforestation and soil damage that may never be repaired.

In May, Glencore informed its shareholders that its total global facilities occupy 2.1 million hectares (ha), of which it acknowledges having environmentally impacted 103,000 ha and claims to have rehabilitated 36,000 ha to date. Additionally, it states that in 2022, it invested USD 2.7 billion in reclaiming lands affected by its fossil fuel businesses, which resulted in the recovery of only 1,863 ha in various parts of the world. However, it acknowledges that efforts need to be intensified over the next 3 to 5 years for the reforestation programs to yield significant results.

In Colombia, the situation does not seem to bring as much optimism. The three coal mines owned by the Swiss multinational occupy 87,667 ha, not including their ports and railways, and their operations have deeply affected the tropical dry forest and neighbouring communities. Meanwhile, the reforestation plans reported by their subsidiary companies, Cerrejon and Prodeco, have yielded discouraging results and an uncertain future, as it is unclear whether Glencore has plans to fully repair the damage caused to these ecosystems once they return their concessions to the state, or the timeframe it would take to address these environmental damages.

This is particularly concerning because the mining giant has ceased its extraction operations in the Cesar department in northern Colombia and claims that it will stop mining at El Cerrejon by no later than 2035; yet, their environmental commitments to the Colombian government have a very short timeframe in relation to the time needed for the recovery of the affected tropical dry forest, which could span generations. According to a detailed review of the public information provided by Glencore, their advertised environmental projects have only reforested 3,898.58 ha at an approximate rate of 133.5 ha per year. If this rate continues, the rehabilitation of the area affected by their mines in northern Colombia would take approximately 656.6 years, an impossible timeline for any human-created organization to fulfil.

Cutting down forests to plunder the subsoil

In 2022, it was the year with the highest global demand for coal in history: over 8.3 billion tons were burned in thermal power plants around the world to generate approximately 10,440 Terawatt-hours (TWh), roughly 36% of global energy demand, according to the International Energy Agency. A significant portion of this fuel was extracted from poor countries, such as Colombia, which allow large companies to extract it from the subsoil at a low operating cost but at a high environmental cost. According to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), last year, 26.5 million tons of thermal coal were exported from the South American country to meet this demand. Of this amount, 22.9 million tons were traded by the Swiss multinational Glencore, the world’s largest mining company, after being extracted from the departments of La Guajira and Cesar, as reported by the National Directorate of Taxes and Customs (DIAN).

However, the open-pit mining carried out by multinational companies in northern Colombia to extract all this coal can only be done at the expense of the forests and fertile soil in the areas where the mine extraction pits operate, leaving severe environmental issues for nearby communities. For over four decades, Glencore, other mining giants, and the companies that came before them have massively deforested these ecosystems to remove the layers of soil beneath which the coal is found. This has involved the elimination of extensive areas where plants and trees grew naturally, causing irreparable damage by weakening the soil and thereby increasing erosion and desertification.

Regarding this, Efrén David Gómez Arévalo, a geologist from the National University of Colombia, states:

«The vegetation, when directly eliminated, produces impacts on the ecology of the area: forests, grasslands. Water sources are eliminated. In nature, everything is interconnected, so fluvial ecosystems are also degraded, water discharges, with the possibility of water shortages for populations, affecting fauna, and reducing biodiversity.»

A history of logging to extract coal

Glencore arrived in Colombia in 1995 when it purchased the Prodeco Group, turning it into one of its subsidiaries. With this move, the Swiss multinational took control of the La Jagua and Calenturitas mines, located in the Cesar department and operated by Prodeco until now, despite this company announcing the closure of these facilities in September 2021. At the same time, Glencore also acquired a significant portion of El Cerrejon, the largest open-pit coal mine in Latin America, located in the La Guajira department and currently operated by Carbones del Cerrejon Limited. The latter company is now also a subsidiary of Glencore, after the Swiss multinational acquired 100% of its shares through a multimillion-dollar purchase from the two-thirds owned by the Australian BHP Billiton and the British Anglo-American PLC on January 11, 2022.

According to the National Planning Department, the process for exporting coal from the El Cerrejon mine began in 1976 and from La Jagua and Calenturitas in 1985. In all three cases, the mining companies arrived as soon as concession contracts were signed with the Colombian government and proceeded to open what would later become the open-pit extraction sites. Large quantities of trees were cleared for this using both hand tools and heavy machinery. Then bulldozers and backhoes were used to remove the soil and soil layers down to the underground rocks, which would later be drilled to implant explosives and detonate them, allowing the operation in the coal pits. Since then, this process has not stopped.

In 1984, the first shipment of thermal coal was exported from El Cerrejon, and the promise of a bright future for Colombia, bolstered by royalties, coupled with the growing global demand for this fuel, led to the expansion of the pits. By the mid-1990s, the mining pit had already consumed a significant part of La Guajira and had put El Cerrejon at the top of the list of the world’s largest open-pit coal mines. La Jagua, located a little further south near the Perijá mountain range, reached the fourth position.

Today, when several of the world’s major economies have built their own mega-mines to meet their internal coal demand, relegating Colombia’s largest mine to tenth place on the list, El Cerrejon has an estimated depth of 240 meters and covers an exploitation area of 69,000 hectares. In other words, it is larger than cities like Frankfurt, Cape Town, Quebec, Brasilia, Beirut, or Medellin. If we were to move the Eiffel Tower from Paris to the bottom of the deepest mining pit, it would protrude less than a third (97.5 meters) of the iconic building.

Throughout this process, in addition to the loss of territory for the communities that traditionally inhabited this area of Colombia, thousands of native trees like the guayacan, carreto, ceiba majagua, and quebracho were cut down, as well as species with some degree of recognized threat by Colombian environmental authorities, such as the ceiba tolua, moncoro, and algarrobo. The local tropical dry forest ecosystems are likely never to recover from these actions.

Licensed to Log

Jakeline Romero Epiayú, an indigenous leader from La Guajira, remembers:

«As members of communities […] we have lived for the past 30 years knowing and understanding all the implications of having a mining company in the territory […] There is no way to hide the impacts on the life, culture, economy, spirituality, and the environment of the Wayúu people in this mining area.»

In 2014, Cerrejon obtained permission from the Autonomous Regional Corporation of La Guajira (Corpoguajira), the environmental authority in that region of Colombia, to begin logging native forests near Jakeline’s ancestral territory. Glencore cleared an area of 155.2 hectares (1.5 km²), equivalent to the size of 217 soccer fields.

Then, in 2016, the mining company received authorization to dam, channel, and divert the Bruno stream over a 3.6 km stretch. This permit was granted by the National Authority for Environmental Licenses (ANLA) and Corpoguajira, with the aim of accessing over 40 million tons of coal estimated to be under the riverbed. Furthermore, four years later, in 2020, ANLA had to impose a series of measures on Glencore to ensure compliance with minimum environmental management standards for these clearances. After reviewing the company’s reforestation efforts, it concluded that «the projected area for rehabilitation during 2020 corresponds to a total of 25 hectares, of which, as of February 24, 2020, [Cerrejon] stated to have rehabilitated 4.»

The restoration work included filling and stabilizing the lands, applying a layer of soil, and planting some trees. However, ANLA found that in the areas where these activities took place, the fertile layer installed by the company had an average depth of only 30 cm, which contrasts with the accounts of the people who were responsible for removing what was naturally present in this area of La Guajira to make way for the mine.

José Brito is a 64-year-old man, tall, with a deep voice, and originally from Fonseca (La Guajira), who worked from 1983 and for over thirty years at El Cerrejon. He recalls that people in the area used to make a living from agriculture and fishing, and with the arrival of the mine, one of the first things that workers like him, hired to operate heavy machinery in the early stages, were instructed to do was to remove the vegetation and fertile soil to begin the coal race:

«There’s the vegetative layer, where you plant; after removing that vegetative layer, you reach the mineral layer, where the crystalline silica is; and then, in this case, there’s the coal […] We had to remove a vegetative layer that was around two meters and something, so that means it was a very productive area.»

Everything seems to indicate that the «vegetative layer» that José refers to is none other than the fertile soil that existed at the time. Four decades later, Glencore is replacing about 2.5 meters of this resource with a layer of just 30 cm, brought in from other areas, to plant some undisclosed tree species and meet unambitious goals the company has set for itself within the few environmental commitments it has made with Colombia.

Likewise, Jélix Torres, another former worker from the early days of El Cerrejon who now resigns himself to living with serious illnesses due to his work there, remembers with great sadness:

«In La Guajira, all kinds of products are produced. We have a variety of climates, vegetation, birds, everything. It’s a very beautiful department, and the part we destroyed to create the mine was one of the most beautiful parts of La Guajira because it was at the foot of the mountain range […] We had to destroy all that […] Mining is harmful in every way because it pollutes the environment, it’s harmful because it destroys it, and I was part of it because I was one of the people who deforested the area where the mine was created.»

Cerrejón did not respond to a right to petition submitted by El Turbión, nor any of the emails sent to the company, so it was necessary to rely on the data published on its website for this investigation.

According to El Cerrejon’s sustainability reports, 266,000 native plants were planted in 2021, and in 2022, 700 hectares of tropical dry forest were restored by three community associations. In the same vein, the «Sustainability Report 2022» presented by Glencore’s board of directors for its shareholders states:

«Cerrejon, in Colombia, planted over 585,000 native trees of the tropical dry forest in La Guajira during 2022. The planting was carried out in around 700 hectares that are part of the land rehabilitation activities where mining activities were previously carried out.»

However, forty years after mining activities began, this effort appears insignificant compared to the more than 69,000 ha occupied by El Cerrejon’s facilities and extraction pits. According to the sustainability reports published by the company, between 2005 and 2022, their reforestation plans covered only 2,764.5 ha, meaning they were being done at a rate of 153.58 ha per year. Restoring the area occupied by the mine would take 449 years if the pace isn’t accelerated.

Neglected Warnings

In the neighboring department of Cesar, things have not been better. In the 1990s, as the La Jagua and Calenturitas mines were expanding to colossal proportions, small coal-mining companies were devoured by groups like Prodeco, which were then acquired by large multinational corporations, without resolving the damage caused during years of extraction.

Jesualdo Vega, a resident of the El Hatillo community located next to the Calenturitas mine, has been fighting for decades for proper resettlement for the people living there since before the arrival of the multinationals. He recalls what the area used to be like:

«You could grow crops. People would go home and feel at ease because, at that time, bartering was common: you’d give something to your neighbours, exchange items. But all of that has changed over time.»

On November 6, 1991, an environmental impact report presented by engineer Orlando Oliveros Urieta, who was then the technical deputy director of the Autonomous Corporation of Cesar (Corpocesar), the environmental authority in that region of Colombia, warned that:

«The removal of the vegetative layer will affect the quality of the landscape, and, in particular, watercourses, as suspended material is incorporated due to erosion […] The clearing activities involve the removal of the vegetative layer of the soil, which generally consists of trees, shrubs, and succulent vegetation, and when removed, it destabilizes the soil by breaking down the particles, thus facilitating erosion and sediment transport phenomena.»

Four years later, Glencore would acquire the Prodeco Group, including its environmental and social liabilities. There is no way that the Swiss company was unaware of this report or the damages caused in the tropical dry forest of the Cesar department during the initial years of operation. However, they did not initiate any reforestation program until 2010, claiming to have rehabilitated 26 hectares, as per the information in the sustainability reports published by the company.

Despite this, Glencore’s operation in the La Jagua and Calenturitas mines continued to expand for years, with the former reaching approximately 12,000 ha and the latter at least 2,700 ha. Together, they produced up to 19.5 million tons of coal annually, as was the case in 2014, and are estimated to have reserves of an additional 135 million tons.

To achieve these numbers, and similarly to what happened in La Guajira, the Swiss mining company cut down thousands of trees and removed the fertile soil layer to expose the excavation pits from which the fuel for the world’s energy demand would be extracted. This continued for a quarter of a century, and the expansion of mining and the destruction of the tropical dry forest did not stop during all that time.

It wasn’t until 2020 that things began to change. The drop in international coal prices, which had been ongoing since the previous year, led Glencore’s management to announce mine closures worldwide, under the guise of environmental concerns but likely driven by a desire to reduce production to increase coal prices on the world’s major stock exchanges. In March of that year, as the COVID-19 pandemic-related lockdowns were just beginning, Prodeco requested authorization from Colombia’s National Mining Agency (ANM) to suspend its operations. However, the government entity rejected this request due to the potential consequences for Colombia’s fragile economy.

A year and a half later, in September 2021, the company announced the closure of its mining activities in Cesar, resulting in the firing of over 7,000 workers and relinquishing five of its mining titles, a situation unprecedented in Colombia. The ANM of the Duque government ultimately accepted the surrender of three of the titles, and to this day, the National Environmental Licensing Authority (ANLA) is engaged in a contentious legal battle to force Glencore to clarify the measures for ecosystem restoration with the aim of returning the concession areas. Prodeco now manages the Calenturitas and La Jagua mines, asserting that they no longer extract coal from there, and the few employees it retains are responsible for proper maintenance to prevent further damage to the excavation pits, which could lead to a major disaster in the area.

Despite all this, none of Prodeco’s public documents make it clear what the transition plan entails regarding the return of the mines to the state. Furthermore, it does not specify the measures being implemented for reforestation in the affected areas, nor does it present a single indicator that would allow the verification of compliance with the environmental actions the company advertises on social media and various media outlets.

As a result, El Turbión submitted a formal request to Prodeco for clarification on the actions taken to recover the deforested areas and the amount of money invested in this endeavor. In a very concise response, a subsidiary of Glencore stated:

«The mining operations of the Prodeco Group in the Calenturitas and La Jagua mines were initially suspended in March 2020 and later terminated definitively in September 2021, as a result of the ANM’s acceptance of the resignation presented in relation to Mining Contracts 044/89, 285/95, and 109/90 […] They have their respective Environmental Management Plan, the latest updates of which were approved by the ANLA through Resolutions 453 of April 28, 2016 (Calenturitas Mine) and Resolution 1343 of July 9, 2019 (La Jagua Mine) […] with their respective closure, dismantling, and abandonment plan, which contemplates the progressive closure sequence and the sequence for morphological rehabilitation, closure of dumps, backfilling areas, and exploitation pit for the execution of final closure […] There are rehabilitation plans that include, among other actions, reforestation of the intervened areas.»

However, the unified environmental management plan for the La Jagua mine primarily outlines reforestation activities related to sterile deposits, which are areas used as dumpsites for crushed rock and residual coal that cannot be sold or exported. Nevertheless, it remains unclear what will be done with the excavation pits, whether it is possible to definitively rehabilitate these lands, how long Glencore’s involvement in the reforestation process will extend, and whether these efforts aim to restore the tropical dry forest.

In 2019, the National Environmental Licensing Authority (ANLA) presented its diagnosis of the areas affected by the La Jagua mine and the work that was underway at that time to repair the ecosystems impacted by mining for the purpose of updating the environmental management plan. The document states:

«Currently, geomorphological restoration and/or soil extension and/or reforestation activities are taking place in the Santafé, Oriental, Tesoro, and Antigua Pista deposits; inactive dumpsites CMU [Consorcio Minero Unido] and Sur are revegetated; the Cumbres and Aeropuerto dumpsites are reforested.»

Furthermore, according to the ANLA document, these activities began in 2018 and are expected to continue until 2028. They will encompass 769.4 ha of the mentioned areas, along with an additional 272.7 ha where sterile material from the dumpsites will be partially used to fill one of the former extraction pits, followed by soil placement and, in Prodeco’s terms, «revegetation.» These areas amount to just 1,042.1 ha, representing a little over 8% of the total area affected by the La Jagua mine. Species such as ceiba bonga, ceiba amarilla, campano, higo amarillo, polvillo, and Cañaguate have been planted, as evident from the comparison of data provided to El Turbión by Prodeco and the ANLA.

As for the remaining 92%, it is uncertain what will happen after the indicated date. This is especially concerning because Prodeco’s intervention, as stated in its sustainability reports between 2010 and 2019, has only succeeded in reforesting 1,134.08 ha across the two mining sites in the Cesar department. This equates to just 113.41 ha per year, implying that the restoration of this tropical dry forest would take at least 129 years if the current pace is maintained.

Reforesting La Jagua with palm?

During El Turbión’s visit to the northern Colombian mining corridor, it was observed that the La Jagua mine, which has been closed for two years, now hosts a large oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) plantation. This plantation is located near the Daníes reservoir along the Tucuy River, on land that Prodeco reports as part of an ongoing soil recovery program.

Certainly, this species is not native to this part of the world, and it doesn’t belong to the tropical dry forest habitat. It has been introduced to Colombia for agro-industrial purposes in monoculture plantations, which has been strongly criticized by scientists, environmentalists, and human rights advocates due to its impact on ecosystems and its clear connection to forced displacement of millions of people and other severe human rights violations in various regions of Colombia. According to a 2022 investigation by Mongabay, Colombia is currently the world’s fourth-largest producer of palm oil and has become the Latin American country with the most reported environmental damage related to this product, with 176 reports out of the 298 registered in the region between 2010 and 2021.

Regarding the notion that this crop serves for reforestation in a mining area, the scientific evidence clearly contradicts this. Due to its monoculture characteristics, palm plantations deplete soils, degrade water quality, and worsen greenhouse gas emissions. A study by the School of Biosciences at the University of Nottingham in the UK, coordinated by Dr. Selvakumar Dhandapani, states:

«Tropical peat characteristics are significantly altered by oil palm agriculture relative to forested forms. Such changes in peat characteristics were also significantly correlated with peat microbial community

structure and GHG emissions.»

For this reason, it is at least curious that oil palm is being used in a reforestation program carried out by Glencore, and there is no knowledge of any actions taken by environmental authorities in this regard.

Lack of Interest in Reforestation

On the other hand, the situation in the Calenturitas mine is not more encouraging. Currently, it not only serves as the basis for a unique coal marketing operation where Glencore buys coal from other companies and transports it on its railway to its Puerto Nuevo terminal for worldwide marketing, despite having its mines in Cesar department closed. Still, its environmental management plan sets relatively unambitious reforestation goals for a similar period:

«a) For the removal of woody vegetation cover, carry out a one-to-one compensation (1:1) for each intervened vegetation cover, equivalent to its replacement (protective reforestation) on an area equal to the intervened area of Gallery Forest (2.96 ha), Open Forest (21.82 ha), secondary or transitional vegetation (66.18 ha), wooded pastures (29.61 ha), and weedy pastures (10.79 ha), totalling an area of 131.36 hectares… b) For the impact on plant species classified with some degree of threat, carry out a one-to-three (1:3) compensation, after presenting to this Authority in the development of the project, the quantification of the number of individuals per species classified with some degree of threat that were removed due to mining activities and converted into an area, based on a criterion of a density of 400 individuals/ha, species that should correspond to algarrobo, balsam, ceiba bruja or bonga, ceiba tolúa, solera, olla de mono, palma vino, puy, and vivaseca.»

To date, it is unknown whether Prodeco has submitted the required environmental compensation plan for the impact on threatened species to ANLA, making it impossible to determine how many hectares are planned for intervention and over what time frame.

Endangered Forests

The Colombian tropical dry forest is an ecosystem with extremely low rainfall, where vegetation has adapted to withstand severe droughts and temperatures that are usually above 28°C. It is typically located below 1,000 meters above sea level. The flora is dense and continuous, with plants exhibiting significant adaptive capabilities, shedding leaves during dry season, and regrowing them during the wet season. This ecosystem plays a vital role in capturing and storing large amounts of carbon dioxide, protects against soil erosion and desertification, assists in recycling essential nutrients for life, retains rainwater and groundwater, regulates climate, and serves as habitat for hundreds of animal species, including birds, mammals, and humans. It also provides food for human communities, contributing to their food security and quality of life by yielding fruits such as nispero, caimito, and mamoncillo.

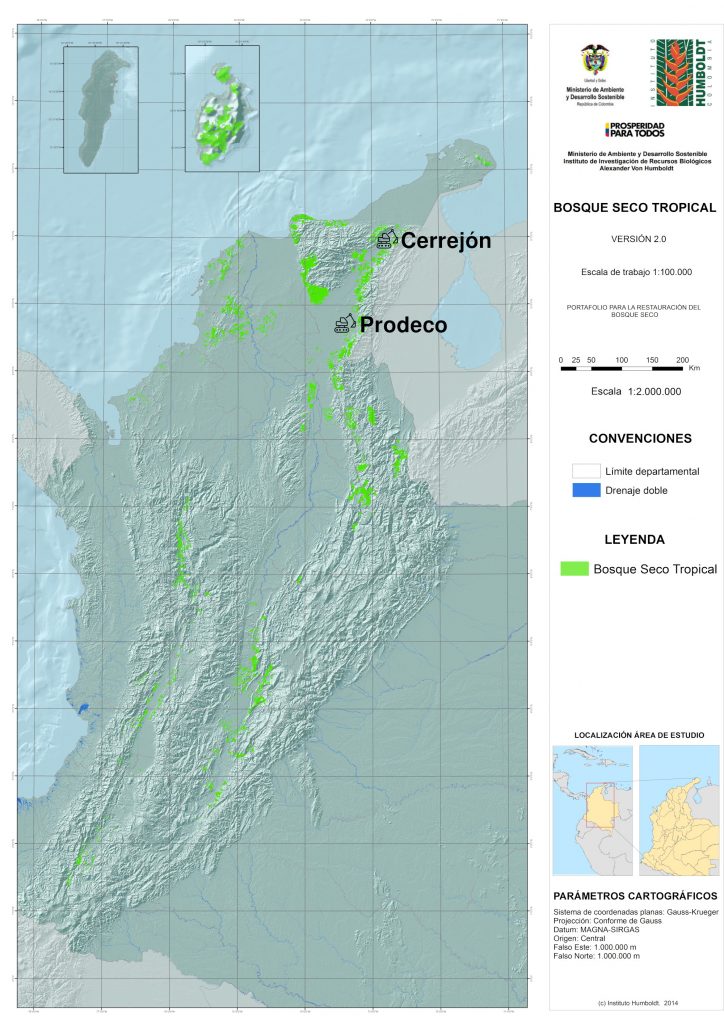

According to the Ministry of the Environment, the tropical dry forest is «considered one of the most degraded, fragmented, and least known ecosystems» in Colombia and is one of the most endangered due to deforestation. Of the approximately 8 million hectares of dry tropical forest in the country, only about 720,000 ha remain, and these are significantly fragmented and dispersed throughout Colombia, with a significant portion located in the Caribbean region. According to the Ministry and the Humboldt Institute, the light green areas on the map represented the portions of tropical dry forest remaining in Colombia in 2014. The situation has worsened since then.

The combined area of the La Jagua, Calenturitas, and El Cerrejón mines is 87,667 hectares. This represents an area where significant numbers of trees have already been cut down, equivalent to 12.1% of Colombia’s total tropical dry forest area. In the past year, mining concession areas in the Cesar department have lost an additional 179 hectares of forest, and La Guajira has lost another 52 hectares, according to alerts collected by the Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) laboratory at the University of Maryland in the United States. The problem continues to worsen day by day.

When observing this region’s data on the Global Forest Watch geoviewer, the loss of vegetation cover has been significant and continuous over just 12 years (2010-2022). This loss will continue if an efficient and effective reforestation plan is not implemented in the region.

Meanwhile, there is no clarity regarding Glencore’s actions to halt the loss of these forests or the environmental authorities, oversight bodies, or the government of Colombia in addressing this serious environmental problem. This is even though the Swiss company controls the largest mining concessions in the country and claims in its 2022 shareholder report that «we are committed to managing our lands in a productive and sustainable manner, including those that have not been subjected to industrial activities.»

Therefore, any action that Glencore takes will have an extremely significant impact on Colombia and its future capacity to support life. Whether they choose to expand their operations, which would involve more deforestation; close mining complexes, as they claim to be doing in Cesar; or rehabilitate vegetation cover in certain areas, as they frequently announce through their social media and sponsored reports in national media, what the Swiss multinational does will decisively impact the future of the tropical dry forest in this corner of South America.

This work is part of the series “Exposing Glencore’s ‘Greenwashing’,” an investigation developed by El Turbión in Colombia, Danwatch in Denmark, and MediaContinente in Sweden on the environmental, labor, and human rights impacts of Glencore’s coal mining operations.

This investigation has been developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

Also, it received support from International Media Support for the initial stage of the investigation.

Si encuentras un error, selecciónalo y presiona Shift + Enter o Haz clic aquí. para informarnos.