Two years have passed since the largest protests in recent history in Colombia and those who suffered physical and psychological injuries due to police violence continue to demand accountability for those responsible and their punishment. For these people, justice remains as elusive as their right to proper healthcare.

At least 116 people fell victim to eye injuries due to the repression carried out by the government of Iván Duque to suppress public dissent. The loss of their eyes remains a painful reminder of the use of brute force and abuse by the state in response to the youth’s outrage and commitment to achieving a fairer society.

«My eyes!»

When the protests erupted in the city of Pasto, in the southwest of Colombia, Clara* was a student and she had never thought about taking to the streets but the aggression of the police against the protesting youth compelled her to join them:

«At first, I just wanted to watch, from home or online, but when I saw that a lot of people were getting involved, I said: ‘people is getting together, it is true.’ […] I saw a young girl in the Carnival Square and a guy recording. And bam! [they shot] tear gas at the girl’s head… she was around 18 to 20 years old… she was young… I watched that video and thought: ‘shit, What happened here?’ So, I started going to the protests, but alone.»

Days passed, and the street fight only grew across the country. Clara was no longer just an observer; she actively participated in the movement of the youth and the First Lines, attending their roadblocks and demonstrations, taking precautions against police violence: «We would go out protected with shields, helmets, and protective goggles. We knew how the Security Forces operate.»

Unfortunately, nothing prepared her for what happened on June 9, 2021. She recalls that on that day, she couldn’t eat from the community pot that other young people like her had organized because the Mobile Anti-Riot Squad (ESMAD) destroyed it and ruined the food, and exhaustion was already taking over her body. That night, the attack by the police was particularly brutal against the protesters:

«I realized my goggles were fogged up, so I said, ‘I have to get out of here…’ because the ESMAD police officers were preparing to keep shooting. I lowered my goggles a bit to clean them, and when I raised my head, the policeman was already there [pointing at me]. It was so strange because I saw how the ‘thing’ [tear gas canister] was coming. I mean, directly, in milliseconds, not enough time to react or anything. You’re just left there like nothing… I said, ‘My eyes!’ and that’s it.»

That night, Clara lost almost all her vision in her right eye and has been dealing with severe health problems since.

According to the House of Memory, a coalition of human rights defenders that emerged during the social upheaval in Pasto, 14 people were reported with physical injuries caused by the excessive force of the ESMAD that night, several of them shot in the head with various types of weapons.

But it didn’t stop there. According to Clara, the police targeted the wounded individuals, and the protesters strongly suspected that plainclothes officers were impersonating medical personnel: «even in the ambulances, they were taking the guys over there and beating them… ¡terrible beatings!» That’s why she refused to be attended to by the Red Cross: «they realized [the paramedics] that I was from the First Line, so they said: ‘you can’t go in an ambulance, you have to go on a motorcycle.'»

Systematic headshots

Five weeks earlier, two young people from Bogotá experienced the same tragedy: they lost an eye due to objects fired by the police at them.

On May 1, 2021, Daniel Jaimes arrived in the Marichuela sector in the Usme locality, in the south of the Colombian capital, to participate in the International Workers’ Day march and protest against: «police abuse, the privatization of education, tax reform, all the reforms that were being launched at that time. It was something that affected us as a community,» as he recalls.

That night, an ESMAD officer fired a tear gas canister at his face, causing serious injuries that, unfortunately, were not promptly treated and led to the loss of his right eye.

For weeks, he faced delays in receiving medical attention and barriers to getting the proper treatment. On top of that, the El Tunal Hospital, where he was initially referred, lacked specialists for this type of injury, and he had to be transferred to the hospital in Facatativa. He says, «I had three facial surgeries in a month. My right eye, nose, cheekbones, orbital floors were affected. I had bleeding in my left eye and a high probability of going blind.»

After a month, he had to continue the procedure in another healthcare facility: «the surgery they performed on me was not very good.»

On the same May 1st, Juan Pablo Fonseca also took to the streets to protest, but in the Usaquén locality in the north of Bogotá. He claims that he participated in the protests because: «we had been facing various difficulties since 2019 and 2020, putting pressure on the authorities to listen to the youth, asking for a series of changes.»

Like Clara and Daniel, Juan Pablo also fell victim to ocular trauma due to the impact of a tear gas canister fired at his face. The young man, who was working as a kitchen assistant at the time, says: «I fortunately […] received appropriate medical care for the severity of what happened to me. Within 15 days, I had already undergone 5 surgeries. It was important at the time because I was at risk of losing my life.»

Nevertheless, he doesn’t hesitate to point out how challenging the process was due to the severity of the injuries caused by the police to his head:

«It was very painful because the fractures in my jaw, in the muscle area, prevented me from opening my mouth. So, I was only eating liquids, and I had lost almost 17 kg. I was hospitalized for a month… For the maxillofacial reconstruction, they opened my head through the crown, had to lift my face to start reducing the fractures, around 72 stitches were made, so the pain was constant. I had a catheter connected to remove the blood from my brain to prevent clots.»

Currently, Daniel and Juan Pablo are part of the Movement in Resistance against Ocular Aggressions (MOCAO), an initiative for victims of eye injuries to report what happened and continue demanding justice.

Months later, police violence persisted, despite calls from the United Nations to the Duque government to stop attacking protesters and ensure justice for the victims.

On August 26, 2021, David Racedo was wounded in Bogotá while protesting in the Usme locality of Bogota. Like the cases mentioned earlier, he also lost one of his eyes due to an object fired by the officers, as he recalls:

«The ESMAD began to throw tear gas indiscriminately, and I was hit in my right eye by a rubber bullet… The First Line youth started shouting, ‘someone is wounded.’ The community helped me.»

David claims that he was initially taken to the Meissen hospital and didn’t receive much medical attention there because «there were no ophthalmology specialists available. So, the next day, they transferred me to El Tunal Hospital. There, an ophthalmologist examined me and said it was a serious wound, but they didn’t have the specialists.» David was eventually treated at the Simón Bolívar Hospital.

For Carolina*, a defender who participated in the Human Rights Verification Committee in the Usme locality, «the demands were quite basic: job opportunities, stable work, food.» However, the Duque government completely refused to listen to the youth. «They [the authorities] had the possibility to stop everything that happened, even the deaths. They could have prevented the eye loss of these young people. This could have been avoided,» she asserts.

Solidarity

Despite all this, what saved countless lives during the 2021 national strike was solidarity. Across the country, dozens of volunteers and healthcare professionals joined forces to protect the injured and provide support. However, the physical, economic, and mental toll left a profound mark on the victims and their families, who are facing difficulties and battling against being forgotten.

In Pasto, groups of volunteers first responders and human rights defenders transported the injured individuals to the House of Memory, where they received refuge and first aid. Martin*, a volunteer who attended to hundreds of wounded people there, says they had: «four, five, six, seven stretchers,» but it was not enough. He adds that most injuries were open wounds from blows, intoxication from inhaling tear gas, and direct head impacts. As he recalls:

«There was a guy… they shot him from 5 meters away in the face. I think he lost four or five teeth, and his face was extremely swollen. They shot him directly in the face. Others were shot in the chest: one almost died because he couldn’t breathe.»

From the House of Memory, those needing hospital care were referred by ambulances. However, most of these were paid for by people who sympathized with the protests because, according to Martin, the authorities provided no help: «Something particular happened here. The mayor’s office [in Pasto] told us there were no ambulances. In fact, people paid for [private] ambulances to take the youngsters because the ambulances from the mayor’s office never showed up.»

Clara claims that the support she received from volunteer doctors was vital in preventing further complications and even in covering her treatment costs:

«When [the doctor] examined me, [he said], ‘this is an emergency… Do you have the money already?’… Imagine a surgery like that, there were like four surgeries at once, and I think it’s already around six or seven million [Colombian pesos]. I had to pay around $400,000, and a lot of people helped me.»

Thanks to this support and the timely surgery she underwent, in which part of her vitreous humor was replaced with synthetic material, Clara was saved from losing her right eye, but she cannot see through it and requires the attention of a specialist doctor that isn’t available in Pasto: «imagine the waiting list they have; so, people try to go to Bogota,» she says.

Nonetheless, the solidarity that allowed the injured youth to be cared for at the House of Memory also attracted police harassment, as Martin recalls:

«They would come with a threatening attitude, like ‘well, what’s happening here?’ and there were constant police patrols. They were always passing by… at one point, we told them: ‘yes, there are injured people here. What’s the problem? If we leave them outside, it’s criminal negligence, and that’s a crime.'»

Even so, the attacks on the wounded individuals didn’t end there. Once they entered the hospital system, they had to endure police officers coming there to look for them among the patients.

Alba*, a doctor at a hospital in Pasto, affirms that in many cases, people would arrive at the hospital with cranioencephalic traumas from head beatings, and there were times when the officers would come there to ask the security guards about people with head, arm, and leg injuries, which several healthcare workers opposed due to the risk it posed to the patients. This led to the creation of a supportive network among the healthcare staff, as Alba narrates: «We started talking about the strike, about the people who were part of it… because we didn’t have the impression that the First Line boys and girls were, as people called them, vandals and thugs.»

Violent medical negligence

For the victims and their families, ocular injuries meant harsh changes. On the one hand, these injuries are visible, which leads to social stigma forever associated with the moment of aggression; and on the other, the barriers to healthcare within the Colombian system and the neglect situation of most hospitals in the country exacerbate the challenges.

In this regard, Alba asserts that for the youth she attended to, these changes were noticeable:

«They would say: ‘now I feel like an old man, having to put eye drops every hour, having to take medication,’ and the families adapting to them, adapting to these new routines of starting to fight with the EPS [Health Promoting Entity, part of the Colombian healthcare system], going into debt to buy medications.»

Daniel Jaimes, on his part, stated that despite being affiliated with the health insurance system as a beneficiary, the treatment costs have been extremely high, and medications have not been provided on time. As he recounts, this led his family to sell some of their belongings to afford the costs:

«They had to do raffles, sell things so that I could have medical care. I felt like a burden to my family; I felt bad, I had many emotional setbacks, depressions. [Because of this] I can say that from being a victim, I became a social activist.»

Carolina denounces the lack of attention in the healthcare system, as when the injured people arrived at medical centres, they received the same response: «if they were members of the First Line or [were there] due to protests, they couldn’t be treated. It happened to us at the CAMI [Integrated Emergency Medical Centre] in Santa Librada; they didn’t attend to them.» She adds that many did receive attention, but they had to present their injuries as traffic accidents: «so that they could receive immediate attention, many colleagues entered as SOAT cases [The mandatory insurance for traffic accidents].»

After leaving the hospital, the victims did not receive adequate professional support or proper follow-up from the healthcare system. They were forced to wait until the EPS had an available appointment slot with a specialist. Thus, the situation of police violence that caused their injuries was compounded by a revictimization by the State due to negligence in healthcare, a burden that these individuals continue to carry.

In this regard, Paulina Farfán, coordinator of the Democracy and Protest area at the Committee for Solidarity with Political Prisoners, a human rights organization that provides legal support to various cases of eye injuries, states:

«Young people have difficulties accessing medical care, they are not provided with medications, and there are delays with surgeries. These kinds of things happen a lot in cases of eye injuries because they [the EPS] claim that these surgeries are very expensive.»

The ESMAD and its excesses

Police violence was so severe that the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH) visited Colombia between June 8 and 10, 2021. After analysing thousands of audios, videos, photographs, and individual and collective testimonies, it was able to «confirm» that the State’s response to the social protests was characterized by the excessive and disproportionate use of force, which in many cases proved lethal.

According to data from the Ministry of Defence during the Duque government (2018-2022), over the three months of the 2021 social uprising, the ESMAD was deployed 1,653 times, resulting in 24 civilians killed and 1,147 others injured within the context of the protests. However, the Ministry did not provide information about the responsible parties or the types of injuries but did report that the police rapidly brought legal charges against at least 224 people, 80 of whom were placed under preventive measures on prison. Today, dozens of young people remain in custody or are entangled in endless legal processes for having participated in these protests.

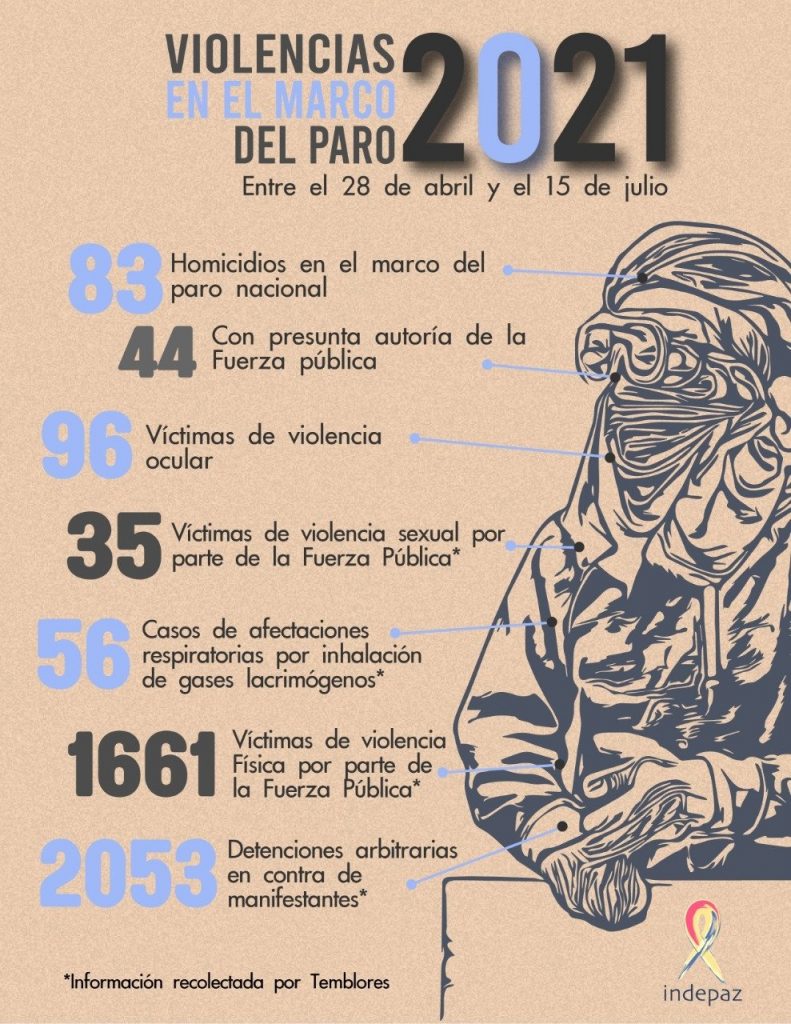

Nevertheless, the balance presented by human rights organizations is quite different. The Institute for Studies on Development and Peace (Indepaz) reported that between April and July 2021, 83 people were killed, with the Security Forces being the alleged perpetrators of 44 homicides.

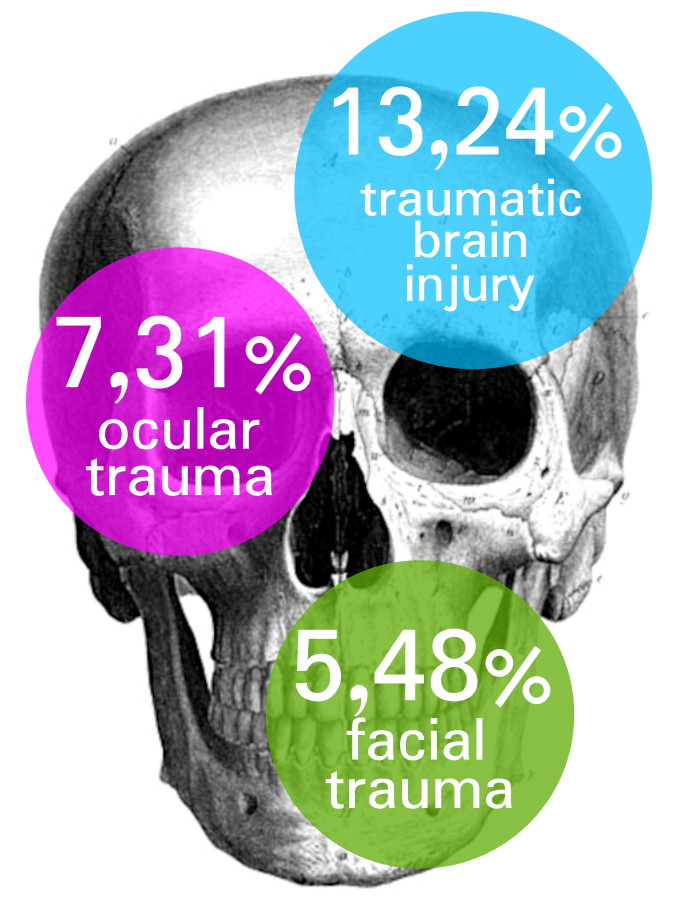

While Indepaz reported 93 ocular injuries, the report: «Repression in sight,» prepared by the Committee for Solidarity with Political Prisoners; the Campaign to Defend Freedom: A Matter for All; MOCAO; and the Centre for Psychosocial Attention, reports a higher number:

«Of the 116 cases, 12 were against women, 70 were against men, and in 34 cases, gender identity could not be established […] non-identification of the victims in many cases was due to prevention and the fear of being prosecuted.»

In Pasto alone, the Casa de la Memoria reports that between April 28 and June 9, 2021, the Police were responsible for: 476 arbitrary detentions, 233 physical injuries, 17 threats, 2 cases of torture, 1 sexual assault, and 2 attacks. Of the injured individuals, 191 were men and 41 were women, with 61 suffering head injuries, representing 26% of those injured.

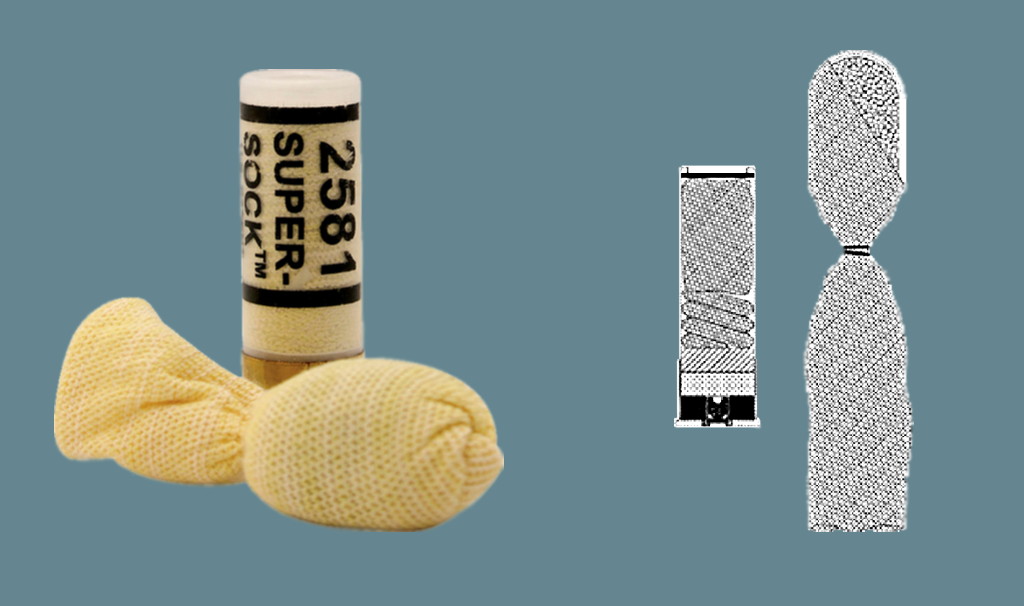

Both the numbers and the testimonies of Clara, Daniel, Juan Pablo, and David, which occurred in different places and on different dates, demonstrate that during the 2021 social uprising, there was a pattern in the actions of the Security Forces, aiming firearms such as tear gas launchers and shotguns at protesters’ heads, firing tear gas and impact munitions such as rubber bullets and other projectiles that caused injuries to the eyes, face, skull, and jaw of the protesting youth.

Two years of adaptation

The damage caused by this type of state criminality has left deep scars on the victims, both due to the injuries to their bodies and the psychosocial impacts they have had to confront during and after their medical treatments. For those who have suffered ocular injuries, rebuilt their life projects, and resumed their daily activities has required a challenging process of learning basic skills. In this regard, Juan Pablo Fonseca explained that this journey has not been easy and detailed how he has coped:

«With this violence, dreams are indeed lost, one’s experience is altered. It’s not easy to live through or come to terms with. Living with this is also a constant learning: how to move, how to regain our motor skills, how to work with that 90° angle instead of 180° [of visual field]. It can be complex not to see on the right side, to know that there’s nothing there. It’s something you learn over time, and you’ll keep learning. The idea is also to strengthen that introspection within oneself.»

For others like Daniel Jaimes, his will to continue as an artist and his dream of becoming a tattoo artist helped him through his process:

«The dreams I had at that time were overshadowed, but with my willpower, the help of psychologists, and [later] getting to know several victims of ocular injuries, I continue with my process of learning to be a tattoo artist. That helped me a lot.»

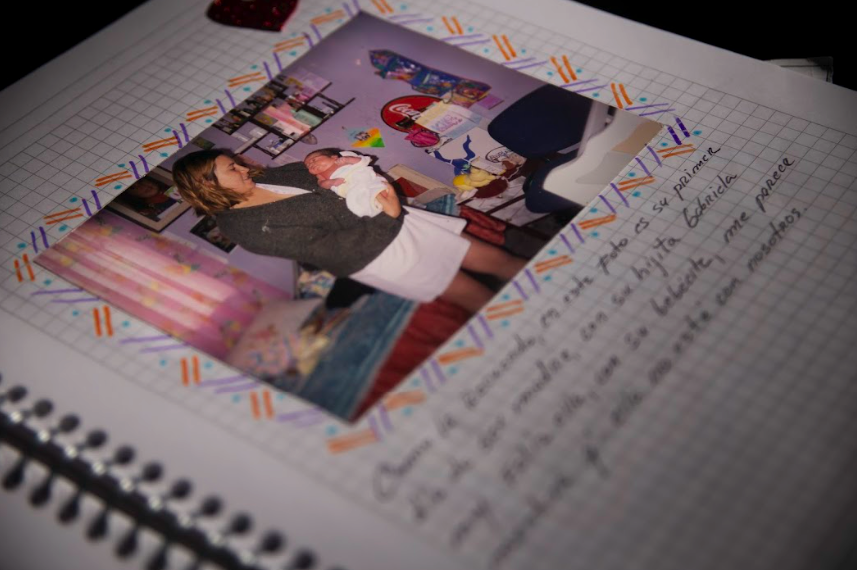

Likewise, David Racedo states that he has adapted to serving the public since he works in commerce, and he has tried to face it positively alongside his mother and daughter, despite how difficult it is: «At first, I felt a bit depressed: people seeing me with this new appearance, with such a severe wound on my face… I knew and was aware that it depended on my attitude.»

On her part, Clara had saved up with several friends and managed to buy a 3D printing machine for her business before the National Strike, but after the police assault, it has become difficult for her to work, and she has debts. The nearly complete loss of vision in her right eye means her left eye has to make an effort it’s not used to, causing her to deal with «awful» headaches when she doesn’t use a patch to cover the injured organ.

Moreover, this situation becomes even more challenging when trying to calibrate the mirrors of the 3D printer or spending long periods in front of a computer screen or tattooing, making work a real challenge. Clara says that «for tattoos, painting, and airbrushing, it’s become very complicated for me. Same with the computer, I can’t use it for long periods either. So, I’ve had to learn more, so to speak.»

But not everyone has been able to adapt. According to members of MOCAO, carrying a lifelong ocular injury has implications, especially without comprehensive care. This is compounded by social burden and stigma from the State. In this regard, Juan Pablo Fonseca expresses how revictimizing the entire process has been:

«After losing an eye, you start to encounter even higher consequences. The lack of psychosocial support… We have to endure stigmatization from all State institutions: healthcare, work, justice. We are experiencing systematic torture.»

In the same vein, Paulina Farfán explains that these ocular traumas have serious impacts on the victims’ health, psychosocial well-being, and lives. She emphasizes that these go beyond mere police abuse:

«We have some elements to consider it as torture: there is both physical and psychological harm, there are patterns that show intent [because] a large portion of ocular injuries were caused by tear gas [which is] used in a non-regulatory manner, and a purpose [because] there is intimidation, there is punishment against those exercising their right to social protest.»

Carolina affirms that many of those who took to the streets in 2021 to protest for their rights and were injured now struggle with deep emotional scars as they demand attention to their mental health to prevent further tragedies:

«As the living conditions [of these individuals] are not being resolved and they continue to seek ways to make a living, this has generated severe mental health problems in young people, to the point of completely losing their sense of life. Here in Usme, a 17-year-old companion decided to leave [committed suicide]. It’s very difficult and harsh to live under these conditions as they are.»

Dr. Alba sees this same issue with mental health and considers that:

«Some of them you don’t really see as living anymore: they die daily, they die in their dreams, they die in their whole being… In other words, they live in death… To this is added the forgetting from us as a society: they were the kids who faced tough situations at the time, they were indeed heroes, and now they are completely forgotten.»

Rebuilding life amid impunity

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH), in its first follow-up report published in 2023, highlighted the scant attention the Colombian state has paid to the recommendations made two years earlier. The CIDH called on the state to investigate and punish those responsible for the killings, disappearances, torture, sexual assaults, and arbitrary detentions suffered by civilians during the 2021 social uprising. The organization particularly drew attention to the impunity in the cases of hundreds of injured individuals, especially those with ocular trauma due to the improper use of less-lethal weapons by the ESMAD and the excesses of the Security Forces during the protest events.

Two years have passed, and progress is scarce in many cases. Some cases have been referred to the Military Criminal Justice System, and in cases of charges, if they reach that stage, actions are treated as personal injuries. According to MOCAO, victims face a lack of willingness from justice operators to impartially investigate cases and punish those responsible.

Paulina Farfán states:

«We have three cases of ocular injuries where the State has been convicted or the responsibility has been attributed to the ESMAD. These three cases are historic, but they’re from quite some time ago, so we can see the very high levels of impunity.»

However, what is most concerning for the human rights defender is that in these three unique cases, there is no criminal responsibility. «There is no individualization of that responsibility, there is no institutional responsibility,» Paulina asserts.

Today, investigations into alleged disciplinary offenses are not progressing, although in 2021, the General Inspection of the Police reported 218 ongoing disciplinary investigations: «103 for abuse of authority, 16 for homicide, 25 for personal injuries, 41 for physical aggression, 3 for sexual harassment.» On this topic, the Office of the Attorney General of Colombia, in response to a request from this media outlet, reports that out of 917 disciplinary processes against the Police, 184 «correspond to actions that were carried out by ESMAD members,» clarifying that in the instruction phase there are 165 cases, of which 117 have been archived; only 12 have reached the judgment phase, and 6 have been transferred to other institutions due to issues of jurisdiction. None of them have resulted in disciplinary sanctions after two years.

Regarding this harsh reality, Dr. Alba acknowledges that while it has been tough for the injured individuals to deal with impunity, «some of them have managed to organize, have managed to create support networks with their peers.» She’s right: Juan Pablo Fonseca explains that by uniting with other victims like him and organizing, he has found the support that neither the State nor society provides:

«We feel that we campaign for empathy [in order] not to feel revictimized, to support each other in this eternal process that this violence has left… We’ve learned a lot, it is unimaginable. All the companions have a lot of knowledge, their life expectations are very enriching, each of them is a very special person with very deep life stories.»

Si encuentras un error, selecciónalo y presiona Shift + Enter o Haz clic aquí. para informarnos.