The incessant consumption of cocaine in the United States and Europe continues to drive the processing of coca base paste in Colombia, which meant that in 2023, an amount of gasoline so large that it could fill and overflow Colombia’s largest lagoon, Lake Tota, with the 1.7 million cubic meters of gasoline used, was poured into the departments with the most coca in the country: Norte de Santander, Nariño, and Putumayo.

Read this article in Spanish

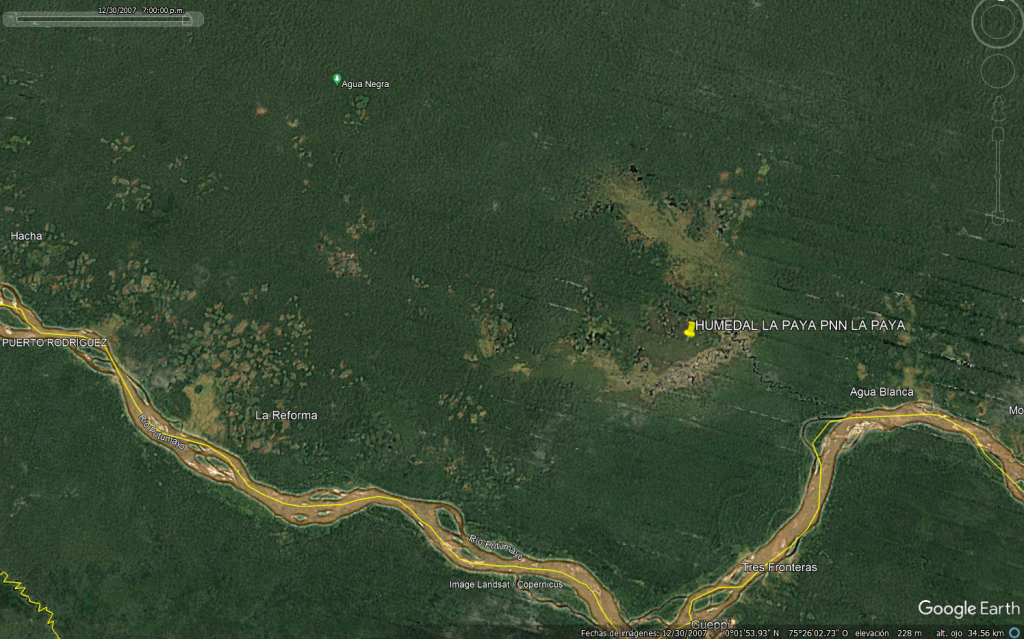

El Turbión visited Puerto Leguízamo, Putumayo, one of the municipalities in this department located on the border with Peru, 550 kilometers from Bogotá. There, it was able to observe how the illicit cocaine economy has contaminated the banks of La Laguna de La Paya, a source of biodiversity in the La Paya National Natural Park. This contamination affects the jungle species and the communities of indigenous peoples such as the Siona, Murui Muina, and Kichwa, among other Amazonian peoples. It also witnessed how the interdiction policy focused on seizing tons of cocaine has temporarily changed the illicit business that fosters environmental crimes along the banks of the Caquetá and Putumayo rivers.

A public health problem that has devastated the Amazon.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), in its 2023 World Drug Report, states that “the population of people who consume cocaine […] in 2021 was estimated at 22 million.” The public health problem is that this number of consumers gradually and steadily increases as there are always new consumers, and some of them end up abusing the alkaloid.

This incessant consumption is reflected in the ravaged jungles of Colombia and Peru. On September 1, 2023, the latest report from the Integrated Monitoring System for Illicit Crops (SIMCI) of the UNODC reported a 13% increase in the area planted with coca in the country, rising from 204,000 hectares in 2021 to 230,000 in 2022.

This increase is directly related to the rise in deforestation. On April 8, 2024, Susana Muhamad, Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development, reported that “Deforestation in Colombia and the Amazon soared in the first quarter with a 40% increase.” The minister blamed the Central General Staff (EMC), a dissident faction of the former FARC-EP led by alias “Iván Mordisco,” stating that this organization is “promoting forest clearing as a mechanism to exert pressure in peace agreement negotiations.” She highlighted that this dissidence has particularly impacted the departments of Meta, Guaviare, and Caquetá, with the latter two being part of the Colombian Amazon.

The Minister’s statements also apply to the department of Putumayo, which is part of the Amazon region and located in the southwest of the country, bordering Ecuador and Peru. According to the Emergency Response Intersectoral Mechanism, an office attached to the European Union, confrontations involving dissident groups in 2021 were concentrated in the municipalities of Puerto Leguízamo, Puerto Asís, and Puerto Guzmán. In these areas, “the number of coca hectares increased by 122.7%, 54%, and 87%, respectively, from 2020 to 2022,” according to the UNODC.

In 2023, Putumayo recorded the highest increase in coca cultivation dynamics with approximately 20,000 hectares, with the municipalities of Puerto Guzmán, Puerto Caicedo, and Puerto Leguízamo being the most affected, having doubled their area compared to 2021. In that year, 204,000 hectares were dedicated to coca leaf cultivation in the country.

La Paya, from Natural Park to Toxic Waste Dump

One of the places experiencing devastation due to coca cultivation is La Paya National Park, one of the 44 natural parks in Colombia and one of the 8 located in the Colombian Amazon. La Paya spans 440,000 hectares and is situated between the Caquetá and Putumayo rivers. It is protected by Agreement 015 of April 25, 1984, signed by the former National Institute of Renewable Natural Resources and the Environment (Inderena), now the Ministry of the Environment.

La Paya boasts an astonishing biological diversity. According to Corpoamazonía, Putumayo is home to 291 species of birds, 58 species of mammals, 17 species of reptiles, 84 species of fish, and nine species of amphibians, many of which inhabit the municipality of Puerto Leguízamo.

An example of this diversity is documented in the scientific article “Mamíferos (Mammalia) del departamento de Putumayo, Colombia”, which lists 66 species of bats, 24 species of rodents, 19 species of carnivores, and 15 species of primates. Puerto Leguízamo stands out as the municipality with the most recorded and threatened species, including the ocelot, jaguar, river otter, giant otter, river dolphin, tapir, and several monkeys such as the spider monkey, white-fronted capuchin, black-headed marmoset, black-headed uakari, and howler monkey. Other species at risk of extinction include the paca, manatee, and anteater.

One of the reasons for its richness is the presence of wetlands and lagoons. The Amazon is the second region contributing the most to the total area of wetlands in Colombia, but most of them are temporary and located around the Caquetá, Vaupés, Apaporis, and Putumayo rivers. In contrast, the La Paya lagoon located in La Paya National Park is characterized by being a non-temporary Amazonian wetland that permanently hosts aquatic flora and fauna, migratory species, and many more mammals and amphibians that inhabit the natural park.

However, all this diversity is affected not only by deforestation and hunting but also by pollution caused by the fertilizers and pesticides used in the over 2000 hectares dedicated to coca cultivation and the millions of liters of gasoline used in the processing of coca leaves into base paste.

In 2004, the Subdirectorate of Regional Affairs and Eradication of the National Directorate of Narcotics, under the Ministry of Justice, stated in a report on illicit crops in Colombia that «98.7% of coca plantations use insecticides or fungicides, 92.5% apply chemical fertilizers, and 95.5% use herbicides.» It is estimated that up to 3.5 million tons of chemical substances per hectare are used each year, but these agrochemicals and pesticides are not the only ones ending up in the soil and rivers. Ether, sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, acetone, caustic soda, cement, lime, and gasoline are also used.

By doing the math solely on the gasoline spilled into the soil, it is estimated that 284 liters of fuel are needed to produce 1 kilogram of coca base, and that from one hectare, 6.5 kilograms of base paste are produced every three months. Therefore, in a year, that same hectare produces 26 kilograms of base paste, requiring 7,436 liters of gasoline.

The demand for gasoline is so high that by 2019, it was calculated that 114.6 million gallons of fuel were smuggled from Ecuador to Colombia annually, and much of this gasoline ended up spilled into the soils and rivers of the Amazon River basin.

Laguna La Paya: an Amazonian wetland contaminated by gasoline

Since 2022, the dissident faction of the former Farc-ep, the self-proclaimed Nueva Marquetalia, has taken control of the Putumayo River basin and maintains control over the southern part of La Paya, including the indigenous reserves La Paya, El Tablero, Cecilia Cocha, El Hacha, and Agua Negra, located to the south of this national park.

In that same year, the highest number of coca crops within the park was recorded: 1,840 hectares, more than double the hectares recorded in 2022, and between January 1 and September 15, 2023, the deforestation monitoring system in the Amazon: Global Forest Watch, recorded over thirty thousand deforestation alerts in La Paya National Park. The highest concentration of alerts occurs in the north and in the southern area, the latter bordering Peru and the Putumayo River.»

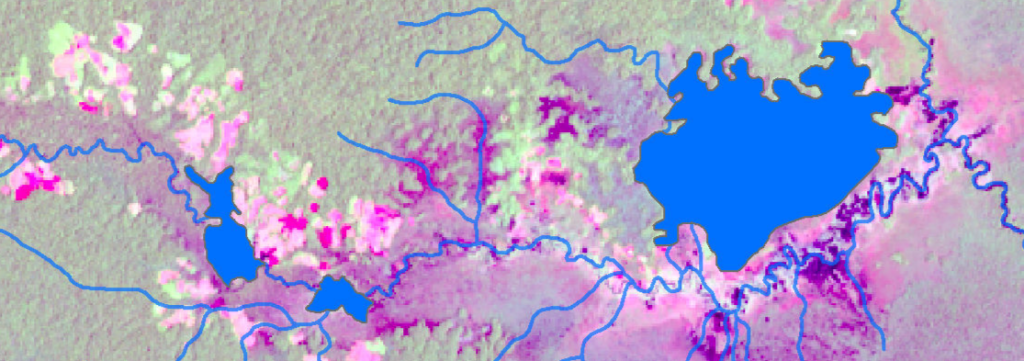

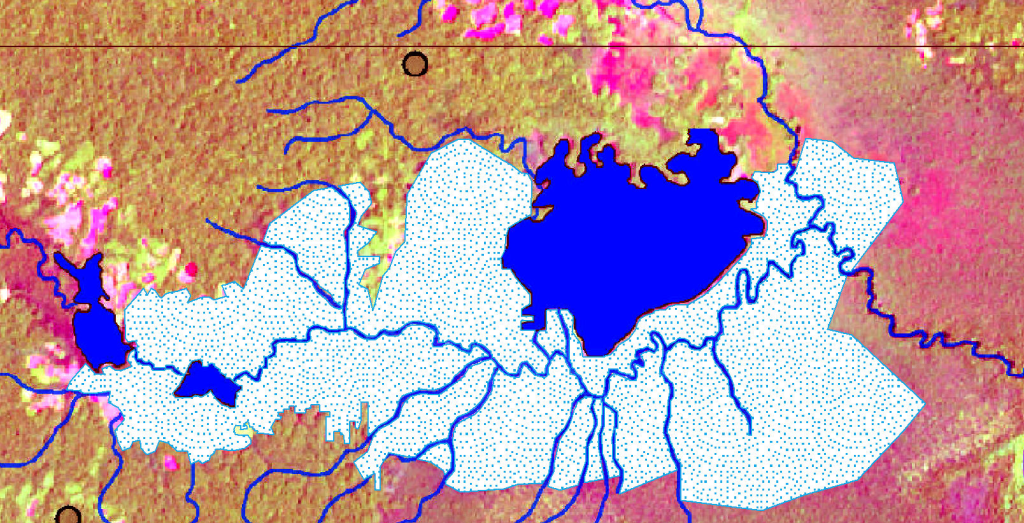

El Turbión obtained access to a detailed map that monitors deforestation due to coca cultivation in Putumayo, updated to May 2024. For security reasons, we will keep the source confidential. When comparing the data from this tool with other open data sources like Global Forest Watch and Google Earth, it reveals that La Paya Lagoon is not reported by these monitoring systems, nor is it noted that deforestation especially affects the lagoon’s shores, a 3,000-hectare body of water located on the southern side of the park, an area influenced by Nueva Marquetalia, through Los Comandos de Frontera, commanded by Giovanny Andrés Rojas, alias «Araña.»

In the cartography, the color pink indicates the degrees of deforestation, and the more intense the pink, the greater the impact. With this in mind, El Turbión calculated the environmental damage in the southern area of La Paya Lagoon and found that over 2,863 hectares have been cleared, just in the delimited area. If coca has been planted in this area, then over 5 million liters of gasoline have been poured into the soil during the processing to obtain base paste, and all this gasoline has seeped into the groundwater and the waters feeding the natural park’s lagoon.

It is evident that the figure of 1,840 hectares of permanent coca crops in 2022 increased in 2023 and has caused the dumping of millions of liters of chemical inputs into bodies of water, as well as the precursors of coca base paste into the lagoon of the national park and its entire ecosystem, also affecting the Putumayo River and downstream waters. However, despite the pollution being constant for decades, it is not analyzed by the competent authorities.

In 2020, the Corporation for the Sustainable Development of the Southern Amazon, Corpoamazonia, characterized 14 bodies of water in the Putumayo department. Notably, only bodies of water near the municipal head of Mocoa were initially evaluated. Furthermore, only 14 bodies of water, including rivers and streams, were analyzed, whereas the department has 39 rivers and more than 18 streams that require detailed characterization.

Corpoamazonía’s study excluded rivers such as the Putumayo, Nasaya, and Mecaya, as well as bodies of water like La Paya Lagoon, and only focused on analyzing discharges of domestic wastewater, when exhaustive characterizations should have been conducted. It has been known for decades that wastewater from coca base paste production filters into the tropical rainforest: residues of fertilizers and pesticides, along with the foul waste from coca production.

Mario*, a Murui Muina indigenous person living near La Paya National Natural Park (PNN La Paya), calls them: «salados.»

Many species have appeared dead, yes, because it’s just pure chemicals that drain into the streams [creeks]. Mostly the fish. Dead. And some animals that come out at night, like the boruga and the tapir, have been seen with strange deformities because they go and suck up all the residue that is thrown out, the chemicals […] so it becomes like ‘salados’ where they dump all that waste and the animals at night start to suck it up, and I think the offspring are coming out with strange phenomena and that is very worrying because it changes the genetics or the species, and that is very serious for us because it is part of our spirituality, and for us to someday hunt a completely deformed animal. …

Near PNN La Paya, the devastation caused by drug trafficking and the control of dissident groups is not only evident but also affects the food sovereignty of the Siona, Murui Muina, and Kichwa peoples, as reflected in Mario’s words:

There is a season when many edible frogs come out, there are places where more than 10,000 – 15,000 frogs gather to mate, but in the last three years, they haven’t gathered again […] where they used to gather to spawn, those territories have been cleared, so they no longer have a place […] it has become a problem for us to feed ourselves, because we collect them and smoke them, and we have food for five or six months, but that hasn’t happened anymore and that is also worrying because when it rains for two or three days, you know that night the edible frogs will gather […] we prepare a special place, and all the families go there at night, each one collects hundreds, but you have to be very careful because many snakes also come to hunt […] the elders make a prayer for the snake to leave while the families collect a basket, and then the snakes come in to eat too, but that has practically decreased.

Between Coca and the Dissidents

The indigenous peoples have lived with the pollution brought by the illicit cocaine trade and under the social control of the dissidents from the former Farc-EP who manage the business. One community in Puerto Leguízamo that has faced these problems is the indigenous community of Guaquira, part of the Murui Muina people and located in the Alto Predio Putumayo Reserve. The reserve, on the banks of the Caquetá River and bordering the Amazonas department, is controlled by the dissidents of the Estado Mayor Central (EMC) through the Carolina Ramírez Front, led by those who have managed the production of the alkaloid since they split from the peace process.

Guaquira began to be populated in 2001 by Murui families. According to Francisco*, the first settlers came for the good living conditions:

They liked it there [Guaquira] because there is a lot of jungle, there was a lot of hunting, a lot of fishing, and also a territory where we could make the chagra to plant our food.

The lives of the first families in the reserve began to change profoundly shortly after arriving at what would become their territory and home. Between 2004 and 2005, due to the lack of economic opportunities and the permission of the Farc-EP, coca cultivation became an alternative, and with it, deforestation began. Francisco recalls:

I think we cleared about 50 hectares. For example, I cultivated two hectares that first year, and the jungle can sustain the coca leaf several times, so I used that same spot the following year and the next, or we moved, and it is still there.

However, there is a difference between the coca crops of families living in coca enclaves, who usually cultivate two to three hectares, and the coca plantations and laboratories owned by settlers who follow the rules of the front led by «Danilo Alvizú«:

Many people went to work, let’s say, in the work areas, where the leaf is stripped, where it is scraped. Exactly, who owns the crops, who controls them? Well, here… how can I put it? The owners of the coca have owners, I can’t name names, but the owner is controlled by outlaws […] those who are there, the Carolina, are the only ones that remain on that side.

What they did not imagine with the cultivation that allowed them to have income for basic goods was that even their way of eating and their freedom would change, as Camilo* recounts:

Suddenly, everyone had to follow their rules, and at the same time, they were recruiting and prohibiting many things. Suddenly, there was no movement late at night; we are hunters and fishers not only during the day but also at night […] Regarding food, many things are becoming scarce. Every day we get our food from the chagra and the territory and from the creeks and rivers. We don’t do like the non-indigenous people who buy a month’s worth of groceries or two months’. We go to the territory every day, get our food, and bring it to our children. And today, in some communities, that can no longer be done, it can no longer be done…

because on one side, there is a threat to the leaders, there are restrictions so that our authorities, our elders, cannot sit with the comunity in the malocas because they [dissidents] know that it strengthens us there. And they have already prevented them from performing their rituals; they even give a family an hour a week to go to the territory, and they have to hurry and return straight back because if they wander off, they might step on a mine. That is happening in Guaquira.

Social control through force and fear continues. After the peace agreement, the dissidents have threatened to kill and attacked those who want to leave the illicit business through the National Comprehensive Program for the Substitution of Illicit Crops (PNIS). However, conditions are changing, and today the illicit cocaine business does not operate as it used to, as Camilo* explains:

Because if we worked the coca, we produced the product, and it was like having money because near where we live there is a settlement where they would exchange everything for that product. Now, everything has collapsed; there is nothing for us, neither to take out that product nor to go and exchange it.

For years, families in Guaquira sold their harvest of leaves or base paste every three months, but today there is no flow of buyers, and even the large coca plantations owned by coca owners that obey the dissidents do not operate as they used to.

For Martha*, a Korebajú indigenous person, this has presented an opportunity to strengthen family ties and the unique practices of her Amazonian people, highlighting the need for support from the state in this regard.

That was very different before; it was us with our sons and daughters, but later, when we saw the money, we looked for workers to always have food, so we stopped planting food and switched to other crops, hiring settlers or people from the same community. Yes, it has affected us. […] Let’s say mostly the culture, our experiences, and also the chagra, the traditional drink, but now they are returning to the chagras. The young people are going out to fish again; they are enthusiastic about fishing and accompanying their elders, some of them, not many, but we are on that path now. So, in any case, we need support from some entity to help us strengthen, let’s say, the cultural aspect most of all.

Today, the coca fields are abandoned, the furrows are neither cleaned nor fertilized, but the consequences in the territory are noticeable for Francisco:

The lands where we used a lot of herbicide are no longer the same. The trees that grow [in areas deforested by crops] are shorter or more stunted. […] The noise of chainsaws, brush cutters, and the smell of gasoline scared away the animals, so there were no monkeys or borugas near the community.

The New Marquetalia controls coca fields in Peru

It’s not just difficult for the EMC dissidents to maintain the flow of cocaine they once had in Guaquirá, which supplied the cocaine route to Brazil; the route controlled by the New Marquetalia dissidents on the border with Peru also faces problems apparently caused by interdiction as a drug war strategy.

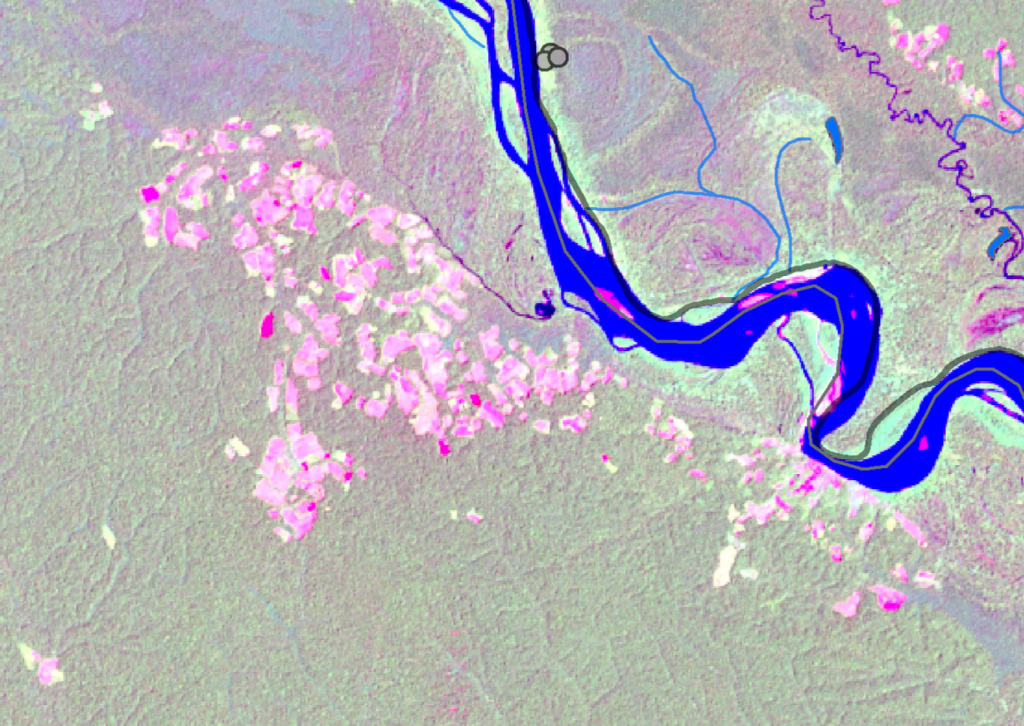

Mario asserts that there are thousands of hectares in Pacora, Peru, jungle inhabited by the Kichwa people and located in front of Puerto Leguízamo. For several years, there have been reports of extensive coca fields and that those in control are the Border Commands, a dissident group part of the New Marquetalia led by Iván Márquez, the former guerrilla commander of the Farc-EP who formed a dissident group.

Similar to Colombia, some families in the indigenous reserve in Peru have small hectares, while large extensions are dominated by Colombian drug traffickers, Mario claims:

There are thousands of hectares of coca, as if it were a reserve of the Peruvian country, and the owners of these coca fields and labs are Colombians. They arrive and bribe Peruvian indigenous leaders and begin to clear jungle for thousands and thousands of hectares. They leave the wood they extract to rot because they are not interested in it; what interests them is planting coca, producing it, and exporting it through Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, and everywhere.

Satellite images of Pacora confirm the presence of large deforested areas that are likely contaminated with fertilizers, pesticides, cement, gasoline, and acids. These pollutants flow from Puerto Asís to Puerto Leguízamo and then to laboratories along the Putumayo River, including the one in Pacora. This indicates that millions of liters of gasoline have been transported through both ports for drug trafficking over decades, despite Puerto Leguízamo having had the ARC Leguízamo Naval Base since January 26, 1944.

Today, cocaine interdiction has changed the dynamics of drug trafficking, but there have been no reported actions in recent years by this naval base in the media.

Between Recruitment and Chagras

The lack of money in Puerto Leguízamo is evident, and hundreds of coca leaf pickers («raspachines») have been left without work, along with many others who depend on this economy, as Francisco explains:

The cultivation attracts coca leaf pickers, and there was also extensive fishing… because that’s how one worked… you would find 100 people, so to sustain it, there was fishing involved… so that was the income from that side, and it affected us because, let’s say, the new youth got involved in getting addicted to smoking other things.

Multiple sources confirm that there is no work in the large-scale coca fields, which have laboratories and can employ 200 to 300 people continuously throughout the year. Today, they call 100 people every three months, and due to the lack of income sources, recruitment has increased, as Mario describes, estimating that both dissident groups have recruited around 200 young indigenous people this year:

The border commands are working, they are paying them. I think they pay them 2 million pesos at the moment, here… members of the commands have permission to enter for two or three months and leave for 15 days, then come back. But with the dissidence, once you enter, you don’t know if you will come back or not; there’s no return. And with the lack of income, there’s nothing else to do. You enter and never come out. That’s the situation, simply complex.

Despite the difficulties, like Martha, who sees families gradually returning to their traditions and customs to address the needs that existed before the coca economy and its associated problems, Clara*, a Murui Muina woman living in a small community near Puerto Leguízamo and facing Pacora, has seen opportunities apart from coca cultivation, even before the business became uncertain.

Clara’s community, seeing the problems faced by neighboring communities, decided to reclaim the land they arrived at over a decade ago, and it has yielded results. Today, several monkeys are attracted by the pineapples grown by women in the chagra – cultivated area- and by the fruits of uva caimarón and caimo trees planted near the community by men, alongside cedar and yellow guayacan. For Clara, they are once again living according to their ways. However, she observes that indigenous women from other communities are bearing the brunt of the changes:

[Men] haven’t changed. Right now, because they don’t have coca, they are just idle, not working or doing anything. I don’t see them going fishing or into the forest… Women, yes, of course, raising animals, like this, supporting the family with the chagra, with yuca, with plantain, just like us, Murui women.

A territory that needs opportunities

In the Colombian Amazon, the Putumayo and Caquetá rivers, on both banks, have been used as corridors for coca cultivation and laboratories, impacting the streams and rivers of their basins, thus affecting the lives of thousands of people. This ecological and social crisis in the Amazon reflects the insatiable global demand for cocaine and serves as a testimony to the ongoing suffering of communities at risk of physical and cultural extermination, who depend on the rainforest for their survival.

Today, as the illicit business transforms under the pressure of interdiction policies, the fight to preserve the ecosystem and indigenous peoples becomes an unavoidable duty of the State. Although these policies have caused instability in the business, it is imperative for the State to offer sustainable and secure alternatives. Indigenous peoples, especially women and leaders, are contributing a ray of hope through their ancestral practices, crucial for the regeneration of both the territory and its people, who deserve a future free from the environmental and social devastation caused by drug trafficking.

This story was produced with the support of Earth Journalism Network.

Si encuentras un error, selecciónalo y presiona Shift + Enter o Haz clic aquí. para informarnos.