Research: Joanna Zapata and Marcela Zuluaga

Audiovisuals: Iván Castaño

Drone footage: Plinio Barraza

Coal mining waste poses a serious problem; companies like the Prodeco Group – Glencore are responsible for changes in water quality, loss of aquatic diversity, and the accumulation of contaminants in the food chain of aquatic species in the communities of Calenturitas and La Jagua in Cesar, and near El Cerrejón in La Guajira.

According to Miguel Ángel Cáceres, a geologist at the National University of Colombia and a member of the Geo-environmental Corporation Terrae, companies exempt themselves from treating their discharges responsibly, «arguing that in their industry, they do not add chemicals in the treatment of the minerals they extract.»

However, Terrae conducted a technical report in 2019 on the surface water quality in areas affected by the El Cerrejón coal project, indicating that while no chemicals are added, the coal industry does contaminate:

Both in Cesar and La Guajira, coals have high contents of heavy metals, including coals that stand out in the content of certain chemicals that can be toxic or harmful to health compared to other coals worldwide.

Cáceres explains that pollution is created by the imbalance caused by mining, impacting life in the region:

The coals and rocks where they are exploited naturally contain elements that are potentially dangerous to human health. They have nickel, lead, cadmium, zinc, various metals, and toxic metalloids. When mining activities begin, they enter into a geochemical imbalance, releasing them into the environment. This is what causes harm to both people and aquatic ecosystems and contributes to air pollution.

Adolfo Enrique Garcerán Fernández, a Yukpa indigenous person and governor of the Sokorpa reserve, experiences the impacts of pollution. He distressingly denounces how coal has contaminated fishing and how the monoculture of oil palm now contributes to water pollution:

It is also affecting everyone who used to live off the river. Before, it was fish, and today it’s sardines. The river is contaminated, and besides that, the monocultures like the oil palm ones are diverting the river. They use chemicals, and those same chemicals end up back in the river. That’s where the sardines come from, already contaminated. It’s making us sick, but they don’t talk about that. So, from our worldview, we know that it has to do with the mining issue that is here.

Misael Socarras, a Wayú leader, reminds us of the sacredness of water for his people, who have inhabited the desert peninsula of La Guajira for hundreds of years and now see their existence compromised by the actions of Glencore – Prodeco:

Water is part of those sacred elements; it represents everything for us. For us, water signifies healing, life, spirit, body, soul, and blood, providing us daily with what we need to continue surviving as the indigenous and ethnic people that we are. Water is everything; without it, we couldn’t live. We don’t perceive water merely as the vital liquid to quench thirst; for us, water embodies everything and is the only thing that cannot be replaced in this life.

How are coal dumps composed?

The rock residues that come out between the coal seams and the coal waste, such as small veins that are not commercialized and are discarded by the industry, are taken to dumps called «sterile,» alluding to their uselessness in the industry and that they «produce nothing.» But, in the words of geologist Miguel Cáceres, this concept distorts reality:

They are not sterile (…) on the contrary, they contain all these chemical elements and heavy metals. Multinationals like Glencore do not treat them at all; they expose them there in the open air, stacked in mountains at least 40 to 50 meters high.

Toxic Substances

In their preliminary assessment of water quality mentioned at the beginning of this text, the Geo-environmental Corporation Terrae associates highly toxic substances:

When large volumes of rock that were previously isolated from the air (oxygen) in the subsurface are exposed on the surface, they will begin to react immediately. Depending on the mineralogical and geochemical composition of the exposed materials, potentially toxic chemicals for humans or ecosystems, such as heavy metals or metalloids like arsenic, can be released and mobilized into the air and surface and groundwater.

An example of the mismatch between the «sterility» asserted by the company and reality is found in the words of Miguel Cáceres regarding the water discharge process in the thermal coal industry, which has further enriched the mining multinational Glencore after the Russo-Ukrainian war:

What they [Glencore – Prodeco] ensure is a chemical characterization that complies with discharge regulations, which is not a guarantee that the water quality of the lagoon will not be affected. Depending on the season, whether it’s raining or not, the lagoon’s water level rises or falls. When it exceeds a certain level, i.e., its maximum overflow height, that water is discharged into streams or bodies of water.

Contamination Overflows

There are impacts on both air and water quality in various springwaters within the mining influence zone. In the case of El Cerrejón, for example, even rainwater from those exploration areas is already loaded with heavy elements or metals that exceed the standard, as reported by the Institute for Studies on Development and Peace, Indepaz, in its report: «If the river sounds, it carries stones.»

Rain is not the only avenue of contamination. Mining companies are required to build sedimentation ponds, which are constructed next to the dumpsite to collect solid materials carried by rainwater. However, when rainwater exceeds the capacity of these ponds, it starts flowing from the higher parts to the lower parts through the coal debris slope.

When this happens, the water carries all the materials from the dumpsite: metals, rocks, and chemical elements. After these solid elements settle, they remain at the bottom of the pond. When the pond overflows, it directly spills into the adjacent watercourse, according to Cáceres.

It is worth clarifying that sedimentation ponds do not undergo any chemical treatment; they simply serve as a mitigation process to prevent pieces of coal or rocks from reaching the watercourses. However, the water carries the entire chemical load from the dumpsites.

It is worth clarifying that sedimentation ponds do not undergo any chemical treatment; they simply serve as a mitigation process to prevent pieces of coal or rocks from reaching the watercourses. However, the water carries the entire chemical load from the dumpsites.

Impact of coal on the rivers of Cesar and La Guajira

In Colombia, there aren’t many studies, and one of the few is the examination of some trace elements in coals from the Cesar and Rancheria basins, conducted by Inés Carmona and Wilmar Morales in 2007.

The researchers collected 29 samples in both mining areas, La Jagua in Cesar, and the Ranchería River basin in La Guajira. They revealed contamination by heavy metals:

Concentrations of mercury, cadmium, selenium, lead, and arsenic above global averages and the Earth’s crust.

The rivers of Cesar, a heritage in danger.

The consultants hired by Emdupar S.A., based on the observation of the water quality state in the Cesar River at the discharge point of «wastewater,» the term used for the waters discarded by the industry, and the laboratory results, deduced that the expected internal biological reactions of the water treatment system are not being met. This is evident in the formation of foams and strong odors.

The irregularity in cleaning certain parts of the system and the absence of sludge removal in all coal discharge ponds cause the pollutant load from the discharges into the river to exceed the parameters established by Decrees 3930 and 4728 of 2010 from the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development.

Karelys Guzmán’s thesis highlights the impact of discharges during droughts and states:

In the summer, the situation worsens for the Guatapurí and Cesar rivers. As their flow decreases, they are unable to dilute the contamination from wastewater, turning them into breeding grounds for disease vectors and causing them to lose all their biological potential.

As a result, there is a bioaccumulation of heavy metals in the food chain. This refers to the process of accumulating chemicals such as heavy metals and some pesticides in living organisms. When an organism is consumed by another in the food chain, the chemical compound is transferred to the consumer.

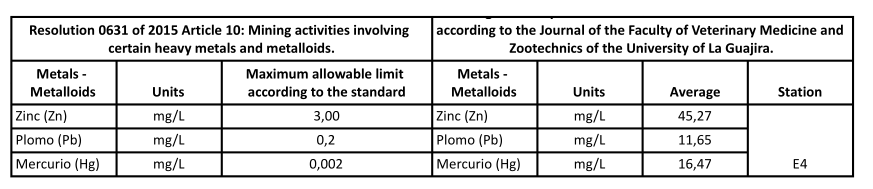

In a 2021 study conducted by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnics at the University of La Guajira on the bioconcentration of heavy metals (Zn, Hg, Pb) in the liver and kidney of the «mojarra rubia» and the «Bagre boca chica» in the Ranchería River, samplings were carried out at four stations along the middle basin of the Ranchería River in La Guajira. The results revealed that concentrations of heavy metals such as lead, zinc, and mercury at the stations exceeded permissible maximum limits.

On its part, the General Comptroller of the Republic conducted a special assessment in three mines in Cesar, and according to geologist Cáceres:

What even international experts found during that assessment is that around this mining complex, there is strong evidence that concentrations of elements such as nickel, selenium, arsenic, manganese, boron increase in surface and groundwater. These elements clearly originate from the rocks containing coal exposed to the environment.

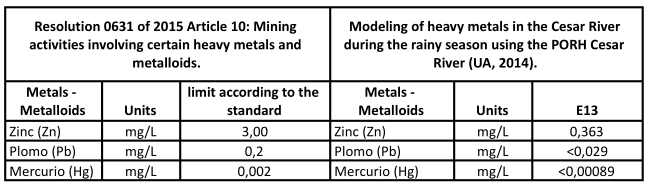

Regarding the Cesar River, the final tributary of the Calenturitas River, the University of the Andes conducted a case study titled «Modeling of Heavy Metals in Rivers. Case Study: Lower Cesar River Basin,» which addressed the presence of heavy metals and metalloids.

In this table, it can be observed that the values of heavy metal discharges in the Cesar River, the final tributary of Calenturitas, do not exceed the limits established by Colombian regulations. However, it is crucial to remember that heavy metals are not metabolized or degraded; they only biomagnify and persist over time, potentially leading to continuous water body contamination.

ANLA had already reported on the contamination caused by Glencore – Prodeco when, in its document «Update on Regional Analysis Report of the Mining Zone of Cesar» published in 2021, it determined that the Potential Alteration Index of Water Quality in the La Jagua de Ibirico and Calenturitas mines is very high. This indicates that the water body experiences significant pressure due to pollutant loads.

On the other hand, investigations conducted by the Geo-environmental Corporation Terrae found elevated concentrations from discharges in coal mining dumpsites in Cesar:

The concentrations for arsenic range from 6.34 to 367.5; for selenium, they oscillate between 4.4 and 45.7; for cadmium, they range from 9.9 to 21.7; and for lead, they are in the range of 24.0 to 104.6. It is evident that the levels of these chemicals, which can be toxic when released into the environment in water, air, and soil, are higher in the rocks of the dumpsites than in the coals.

As a consequence, the high pollutant load of heavy metals, even when it does not exceed the permissible limit on some occasions, persists over time and does not biodegrade. On the contrary, it biomagnifies in the tissues of all higher organisms present in the food chain.

This increase occurs as organisms feed on each other and is mainly manifested in aquatic ecosystems. The process begins when pesticides, heavy metals, or contaminated organic compounds are discharged into a water body, affecting crustaceans, fish, and other aquatic organisms.

The rivers and streams of La Guajira, a reflection of mining

The impact of mining on the Ranchería River is evident in the presence of heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, barium, manganese, iron, and zinc, which exceed the maximum limits established by Resolution 2115 of 2015. This resolution sets acceptable quality criteria for the use of the resource to preserve flora and fauna in freshwater.

However, when comparing the values of heavy metal discharges in sediment from the Ranchería River, according to the journal of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnics at the University of La Guajira and Resolution 0631 of 2015, it is observed that the values of discharges caused by mining activity significantly exceed the limits established by the standard. This means that they will persist over time, affecting the food chain and all life cycles.

And what are the discharge limits in Colombia?

The companies engaged in coal mining do not carry out the geochemical characterization of dumpsites or sedimentation ponds. Additionally, the current water quality index of IDEAM IACAL, the Colombian government agency responsible for environmental studies, does not consider the presence of heavy metals or metalloids, which are the main pollutants in tributaries such as the Cesar, Calenturitas, and Ranchería rivers, as pointed out by Andrés Ángulo in his research on environmental crimes.

In this regard, the expert Miguel Cáceres comments:

This water quality index considers basic parameters such as pH, electrical conductivity, dissolved oxygen, temperature, and nitrogen. The index is designed as an initial approach to understanding water quality. However, from a technical standpoint, this index is not suitable for mining contexts or coal mining.

Glencore – Prodeco does not allow for the assessment of environmental impacts

The difficulty in accessing information about the residual discharges from the mines has been an obstacle to analyzing the impacts and water quality in the communities near the coal mines in Cesar.

Unfortunately, this outlet could not obtain access to the characterization reports of wastewater discharges from the mine, conducted by Prodeco, with the purpose of contrasting the results with the water quality standard for Colombia or with Resolution 0631 of 2015, Article 10, which regulates mining activities, especially regarding certain heavy metals and metalloids, as well as the regulations establishing permissible limits for non-domestic wastewater discharges.

According to the Technical Audit Report on Water and Environmental issues in three coal mines in Cesar, conducted by the General Comptroller of Colombia and Robert Moran in 2015, it is stated that:

In conclusion, the lack of publicly available baseline data. None of the government files contained data from mining companies representing true baseline conditions, meaning data collected before the current mining activities began.

Permissiveness and Regulatory Failures

In addition to pointing out the lack of transparency in regulation and monitoring, the team from the General Comptroller’s Office discovered that these coal companies essentially self-monitor and self-regulate. Furthermore, crucial data is not available to the general public:

Almost all specific site data on water resources had been collected by the mining companies themselves or by consultants they had paid. Ideally, regulatory entities should collect environmental and water data through parties that are technically and economically independent of the coal companies. This audit was, in part, an attempt to gather similar data.

For communities, citizens, and the media, accessing complete and impartial information is challenging. Additionally, regulatory authorities, such as the Environmental Licensing Authority (ANLA), Ministry of Environment, Corpocesar, and Corpoguajira, have not adequately assessed or interpreted environmental data and the water effects of mining for many years.

In this grim scenario, the rivers of Cesar and La Guajira have become silent witnesses to the global voracity for Colombian thermal coal and the state’s permissiveness towards mining-induced pollution.

However, it is Glencore – Prodeco and its boards of directors that have facilitated the discharge of heavy metals into water, contaminating every living being with a toxic sentence that affects the region’s biodiversity and public health. This turns the discharges into an incalculable environmental crime with no solution or improvement plan in the near future.

This work is part of the series “Exposing Glencore’s ‘Greenwashing’,” an investigation developed by El Turbión in Colombia, Danwatch in Denmark, and MediaContinente in Sweden on the environmental, labor, and human rights impacts of Glencore’s coal mining operations.

This investigation has been developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

Also, it received support from International Media Support for the initial stage of the investigation.

Si encuentras un error, selecciónalo y presiona Shift + Enter o Haz clic aquí. para informarnos.