Before the social outbreak in April 2021, the public was aware of the murders of Nicolás Neira, Johnny Silva and Belisario Camayo Guetoto in 2005, Óscar Leonardo Salas en 2006, and Dilan Cruz on November 23, 2019. The Council of State issued even 10 judgments against the Nation between 1993 and 2017, holding the police responsible for murder and serious personal injuries during protests. These state crimes underscore the urgency of a police reform that prevents this state institution from addressing social demands and issues and ensures transparency and accountability of its agents.

A benefit of a reform oriented towards human security would be the reduction of spending on ammunition, which currently only benefits companies supplying Colombia with less-lethal weaponry. These companies secured lucrative contracts before and during the 2021 outbreak. On the other hand, the aim is to prevent a repeat of what former presidents Álvaro Uribe, Juan M. Santos, and Iván Duque did by mobilizing the police to support their government policies without condemning the violence of the ESMAD, resulting in dozens of deaths.

Álvaro Uribe used the ESMAD in the implementation of his democratic security policy, and during his presidential term from 2002 to 2010, this force killed 15 people.

| Nicolás Neira | Bogotá | 2005-05-01 |

| Johny Silva Aranguren | Valle del Cauca | 2005-09-22 |

| Belisasrio Camayo | Cauca | 2005-11-10 |

| Oscar Salas | Bogotá | 2006-03-07 |

| Pedro Pascué Canas | Cauca | 2006-05-16 |

| José Uldaríco Gallego | Cauca | 2006-07-14 |

| Herney Silva Yela | Cauca | 2007-02-19 |

| Jeśus Pérez | Cauca | 2007-02-19 |

| Miriam Banamá Guatiquí (6 ños) | Chocó | 2007-05-26 |

| Laurise Rivera Fontalvo (3 años) | Bolívar | 2007-11-22 |

| Xavier Alfonso Eljach | Bolívar | 2007-11-22 |

| Tarquinas Valencia Ramos | Cauca | 2008-10-12 |

| Mariano Moreno Dizú | Cauca | 2008-10-12 |

| Jesús Antonio Nene | Cauca | 2008-10-17 |

| Ilberto Ipia Ibito | Cauca | 2008-10-17 |

During Juan Manuel Santos’ presidential term from August 7, 2010, to August 7, 2018, the ESMAD caused the deaths of 25 people. The National Agrarian Strike of 2013 alone is associated with the deaths of 12 people.

| Edwin Franco Jaimes | Norte de Santander | 2013-06-22 |

| Dionel Jácome Ortiz | Norte de Santander | 2013-06-22 |

| Diomar Angarita | Norte de Santander | 2013-06-25 |

| Hermides Palacio | Norte de Santander | 2013-06-25 |

| Juan Carlos Lón | Cundinamarca | 2013-08-26 |

| Jeiner Mosquera | Tolima | 2013-08-29 |

| Jhonny Velazco Galvis | Bogotá | 2013-08-29 |

| Christian Jhoan Delgado Wilches | Bogotá | 2013-08-29 |

| Persona No Identificada | Cauca | 2013-09-05 |

| Persona No Identificada | Cauca | 2013-09-05 |

| Persona No Identificada | Cauca | 2013-09-05 |

| Persona No Identificada | Cauca | 2013-09-05 |

| Siberston Guillermo Paví | Cauca | 2015-04-10 |

| Miguel Ángel Barbosa | Bogotá | 2016-04-21 |

| Brayan José Mancilla Ballestas (12 años) | Atlántico | 2016-05-19 |

| Gersain Cerón | Cauca | 2016-06-02 |

| Marco Aurelio Díaz | Cauca | 2016-06-02 |

| Naimén Agustín Lara | Cesar | 2016-07-11 |

| Luís Orlando Saíz | Boyacá | 2016-07-12 |

| Danielñ Felipe Castro (16 años) | Cauca | 2017-05-09 |

| María Efigenia Vasquez | Cauca | 2017-10-08 |

| Christian Stefan González | Nariño | 2018-03-25 |

| Juan José Antonio Mayorga | Nariño | 2018-03-25 |

| Iván Troches Casso | Nariño | 2018-03-25 |

| Persona No Identificada | Nariño | 2018-03-25 |

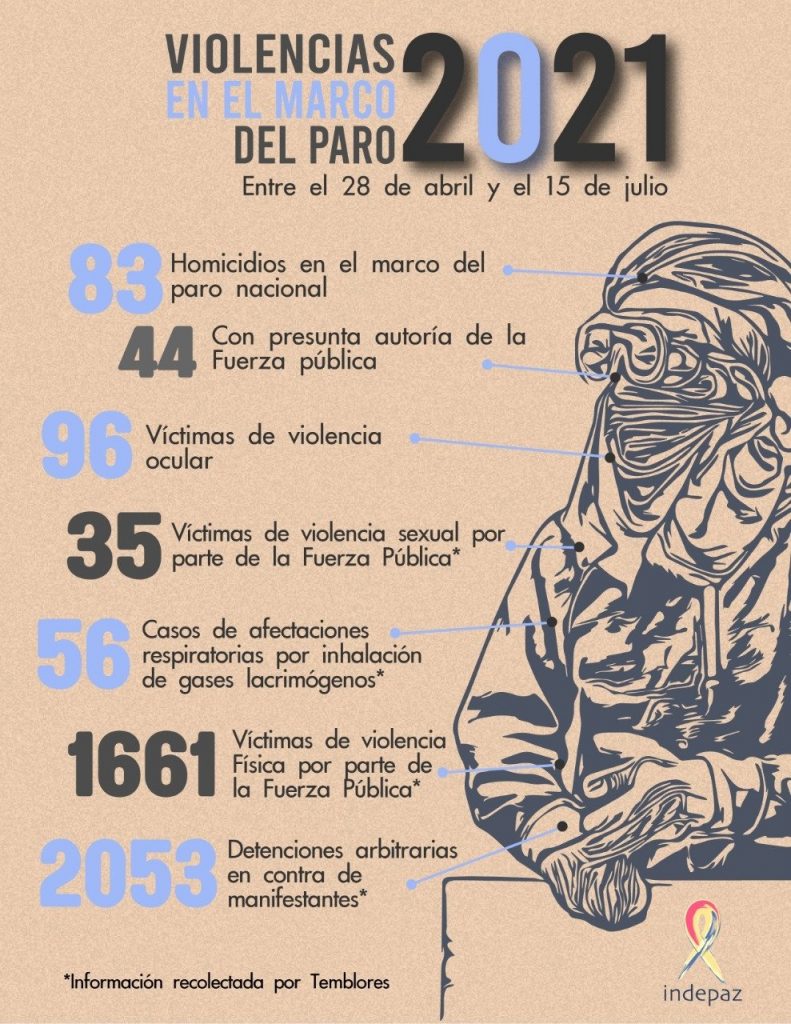

Iván Duque also turned to the ESMAD when the country erupted after attempting to impose a 19% increase in public services and basic food products amid the pandemic, without addressing poverty and hunger. The Institute for Studies on Development and Peace (Indepaz) reported that during the strike, there were 83 homicides, with 44 of them involving the Security Forces. This occurred while spending on non-lethal ammunition was taking place amidst the pandemic.

Firing and bidding non-lethal ammo during the pandemic

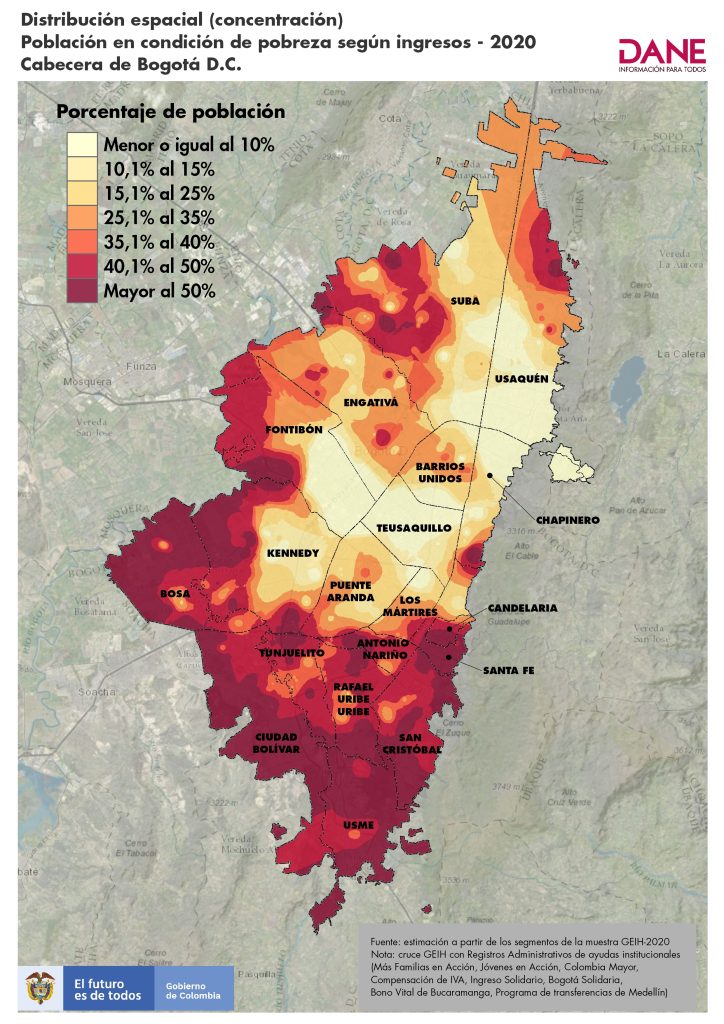

Between 2019 and 2020, according to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), 3.5 million people fell into monetary poverty, and 2.8 million people entered extreme monetary poverty.

Highlighting that Iván Duque invested significant sums while the population needed economic assistance. Former President Juan Manuel Santos had already provided the police with less-lethal weaponry, as denounced by Senator Wilson Arias, who warned about the expenditure of 14 billion dollars on ammunition for the ESMAD.

Today, the anti-riot police force has 25 thousand gas cartridges, 10 thousand stun grenades, 14 thousand multi-impact grenades, and over 12 thousand 12-gauge cartridges, the lethal ammunition that killed the young Dilan Cruz. To add to this, a projected expenditure of two trillion pesos has been planned to purchase 47 thousand gas cartridges, 11 thousand stun grenades, 23,700 marking bullets, 5 thousand multi-impact grenades, and 13,467 12-gauge cartridges.

El Turbión was able to trace on the Colombia Licita website that, in the midst of the pandemic and for the year 2021, Iván Duque tendered 8,583,110,314 pesos for repression measures.

Protective gear and launchers

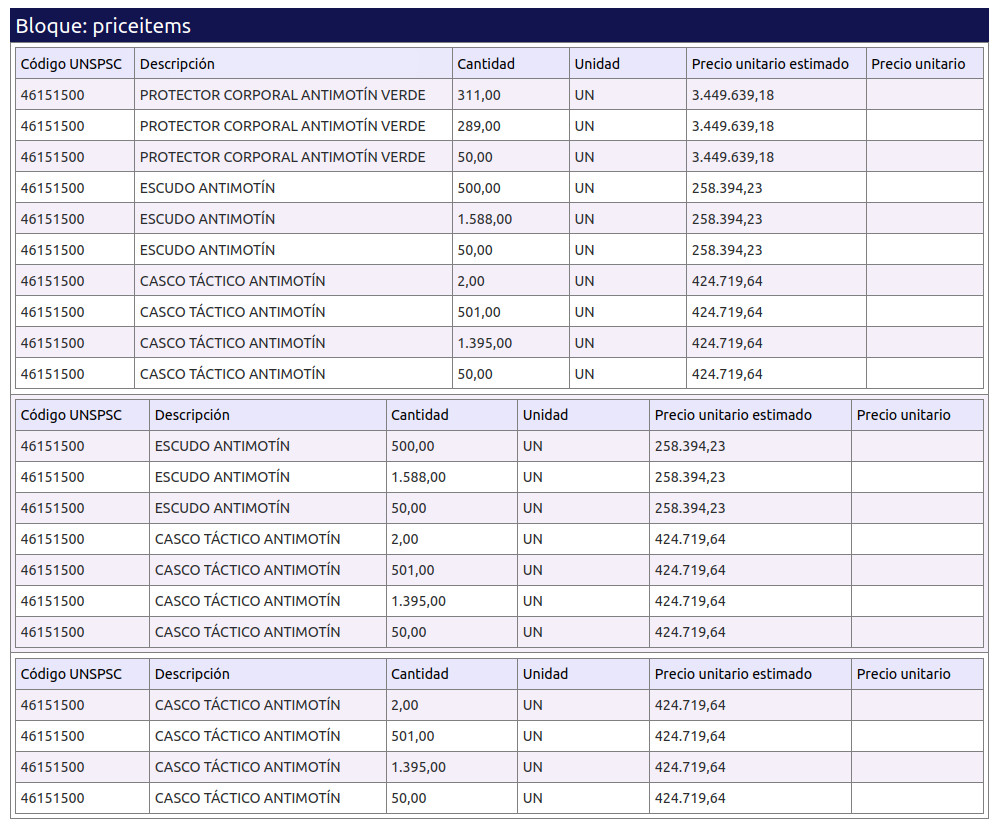

In April 2021, his administration offered 3,622,066,189 pesos for the acquisition of:

- 650 body protectors at 2,242,265 pesos each;

- 2,138 shields at 552,446,863.74 each; and

- 1,948 tactical helmets at 827,353,858 pesos each.

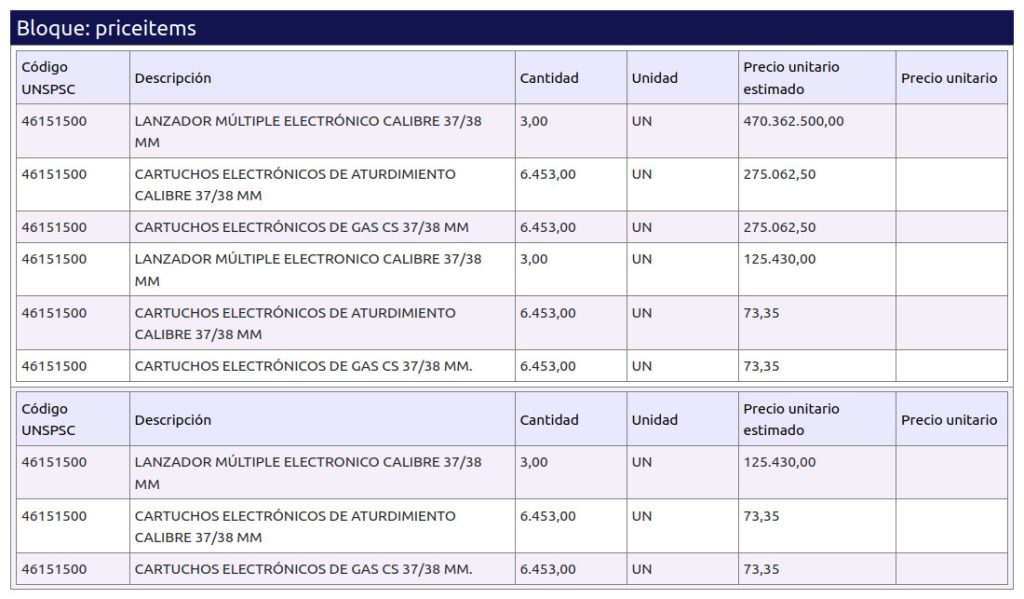

In July of the same year, El Turbión verified that the State tendered 4,961,044,125 pesos for the purchase of anti-riot weapons and invited the U.S. Combined Systems to sell to the Colombian State:

- 3 electronic multiple launchers caliber 37/38 mm: at 1,411,087,500 pesos each

- 6,453 electronic stun cartridges caliber 37/38 mm for 1,774,978,312 pesos, and

- 6,453 CS gas electronic cartridges 37/38 mm for the same value as the stun cartridges.

Companies that profit from repression

Combined Systems, Inc,, an American company, and Condor S/A Industria Química, a Brazilian company, are two of the companies that have benefited by selling less-lethal weapons to suppress protests in Colombia. Although both have not condemned the misuse of this weaponry by the police, they cannot claim ignorance regarding police brutality or the inappropriate use of less-lethal weapons by security forces.

Combined Systems: the invited company

Combined Systems is a leading provider of security equipment to state forces in various countries, including the Estados Unidos, Chile, Colombia, Bahréin, Egipto and Hong Kong. Particularly known for supplying less-lethal ammunition, the company markets launch systems, riot control products, tactical equipment for the police, irritant and smoke munitions, impact munitions, stun grenades, and trauma grenades, according to its website.

It’s also not surprising that Combined Systems does not take any responsibility for the use of its munitions. The company made no comments on the eye injuries caused by the U.S. police in 2020 during the protests that arose after the killing of the African American George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin and the involvement of his colleague J. Alexander Kueng.

The company also did not make any statements regarding the misuse of its ammunition in Chile, where between October 2019 and March 2020, reports indicated 460 eye injuries and 34 deaths.

During this period, Combined Systems sold a thousand tear gas canisters to Chile for $370,000. Captain Patricio Maturana irregularly used at least one of them, shooting Fabiola Campillai in the face on November 26, 2019, as she was leaving for work. This act caused her a traumatic brain injury, multiple fractures in her face, and the rupture of both eye sockets. As a result, she lost her sense of taste, smell, and vision for life.

The Brazilian Condor

Another company benefiting from repression in Colombia and Central and South America is the Brazilian company Condor, founded in 1986. According to the Marketing Director’s résumé, by 2014, the company recorded international sales of $50 million for non-lethal ammunition and weapons. Since 2018, the company has been selling rubber bullets and tear gas grenades to twelve Latin American countries. Between 2020 and 2021, Condor sold ammunition to Colombia worth 1.8 million dollars, becoming its second-largest buyer in those years of pandemic and social protest.

Condor Não-Letal, although offering online courses on its website to operate its products, as well as training both within and outside Brazil, and like Combined Systems, does not comment on the misuse of its non-lethal weapons. Neither does the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Brazil nor the Ministry of Defense, although:

One possible reason for the silence is that the company knows these weapons are lethal and sells them to countries that permit police brutality, allowing the potentially lethal use of these weapons. One such country is Bahrain, as highlighted in Amnesty International’s report, «The Trade of Repression.«

In Bahrain, at least 12 people died after security forces unleashed a wave of repression in response to government protests, including the direct firing of tear gas grenades at protesters and into homes.

In other countries, such as Pakistán (2023), Sudán (2021) and Venezuela (2017), these weapons have been irregularly used without objections.

30 Years of «Disproportionate, Illegitimate, and Violent» Actions

The first condemning ruling against the Nation occurred on January 28, 1993, when the Council of State found the national police guilty of the death of a UPTC student in Tunja.

The ruling, which took six years, also stated that members of the National Police «exceeded» the «internal and social discipline» of the police and «fired on a group of young people, resulting in the death of Tomás Herrera Cantillo.

The ruling adds that the police behavior was inexplicable and emphasizes:

If the police officers were equipped with helmets, protective shields, and even firearms, in addition to being professionally prepared for this type of operation, and if the students never fired at the official agents, the disproportionate, illegitimate, and violent behavior assumed by them in the face of the University students is inexplicable.

While the ruling holds the institution responsible, it does not individualize or seek to identify the responsible party, ensuring impunity and allowing violence to persist.

On June 12, 2017, 14 years after the first ruling, the Council of State held the Mobile Anti-Riot Squad (ESMAD) of the police responsible for the murder of the fifth-semester chemistry student at the University of Valle, Jhonny Silva Aranguren, on September 22, 2005, on the university premises.

(…) from the evidence, we can conclude not only that the Mobile Anti-Riot Squad of Cali entered the university campus, but also that one of its members shot and caused the death of Mr. Jhonny Silva Aranguren, as indicated by the plurality of the testimonies, their concatenation, and coherence.

On that same day, ESMAD seriously injured Germán Eduardo Perdomo Abello, who, according to Forensic Medicine and Sciences, initially received trauma with a stone in his right thigh from the police and subsequently suffered a cranial injury, probably from a tear gas canister:

He receives trauma to the head at approximately 12 cm, receiving medical attention at the Valle del Lili clinic where they diagnose a complicated facial wound, cranial encephalic trauma, contused hematoma right parietal (…) Plastic surgery and daily wound care on the frontal wound, pending check-ups.

A firearm killed Jhonny Silva, and according to the ballistics report presented by the Technical Investigation Corps (CTI) of the Attorney General’s Office, the police, at only «12 meters away,» were firing tear gas canisters at the students’ heads on that occasion, employing combat tactics that resulted in the death of Jhonny Silva.

[The shooter] was in a combat position, either lying down or kneeling at the same level as the victim and located to the left rear of the victim.

In the 2017 ruling, as in 1993, the Council of State characterized the deployment of force by the National Police executed by the ESMAD as «excessive» and «unjust» and added that it is «against the law.» Furthermore, it emphasizes impunity:

A serious and impartial criminal investigation into the circumstances and those responsible for the death of young Jhonny Silva Aranguren was not carried out.» It is also highlighted that his death was deliberately caused by ESMAD members, who, as declared, «fired their firearms directly at the protesters.

Despite the ruling mentioning the excessive police violence, as in 1993, and referring to impunity, it did not seek to identify the perpetrators of the murder, despite it constituting a serious violation of human rights.

The ESMAD does NOT ensure order without violating freedoms

The systematic nature of the police’s violent actions led 49 individuals to file a lawsuit in 2020 before the Civil Chamber of the Superior Court of the Judicial District of Bogotá against the President of the Republic, the Ministers of Defense and Interior, the Mayor’s Office of Bogotá, the Director General of the Police, the Commander General of the Metropolitan Police of Bogotá, the Ombudsman, and the Attorney General of the Nation.

The proponents of the initiative argue that since 2005 and especially in 2019:

In the face of peaceful protests or demonstrations, [the ESMAD] has displayed constant, repetitive, and persistent behaviors to undermine, discourage, and weaken the right to express themselves without fear, demanding policy changes from various authorities.

Among the behaviors that the plaintiffs consider violative are:

- Systematic, violent, and arbitrary intervention by law enforcement in demonstrations and protests.

- «Stigmatization» of those who, without violence, take to the streets to question, refute, and criticize government actions.

- Disproportionate use of force, lethal weapons, and chemicals.

- Illegal and abusive detentions, inhumane, cruel, and degrading treatment.

- Attacks against freedom of expression and the press.

Although the petitioners did not win the lawsuit, on September 22, 2020, the Council of State referred to the ESMAD as a force that does not guarantee the minimum standards of a rule of law and declared it a serious problem:

The vacuum that the ESMAD institution represents, as it is incapable of ensuring order without violating the freedoms and rights of citizens to dissent, as it also does not make appropriate use of the assigned weapons.

10 convictions against the State for police brutality

The teacher at the Universidad Surcolombiana, Germán Alfonso López Daza, compiled all the decisions of the Council of State, and upon reviewing them, evidence of the use of firearms in protests prior to the creation of the ESMAD is apparent, as well as the incorrect use of less-lethal weapons by the police riot squad. This demonstrates that brutality persists, as indicated by the 10 convictions against the State for cases of police brutality.

It is noteworthy that the decisions of the Council of State are not heeded by the police. Therefore, the Supreme Court of Justice, in the ruling of September 22, 2020, demanded that the police implement measures to ensure transparency and accountability in their actions:

Procedures must be implemented to verify the legality and/or proportionality of the use of lethal force exercised by state agents, as well as orders from the chain of command related to the incident (…) once it is known that its security agents used lethal or non-lethal weapons, causing harm to the life and integrity of people, a satisfactory and convincing public explanation of what happened must be provided immediately, and within a period not exceeding six (6) months from the incident, regardless of any investigations that may be taking place, and to refute allegations of their responsibility, through appropriate evidence.

The ruling of the Supreme Court turned out to be in vain for the police during Duque’s administration, who never sanctioned police violence. This violence manifested in systematic attacks to the head and eyes of protesters, resulting in a total of 96 victims of ocular violence in just 4 months.

As a consequence, accountability and the investigation of police responsibility for their crimes are very low:

The Office of the Attorney General of the Nation, in response to a request from this outlet regarding disciplinary proceedings against police officers in the context of the 2021 unrest, reports that: 184 disciplinary proceedings against the police «correspond to actions that were classified as carried out by members of the ESMAD» and informed that there are 165 cases in the instructional stage, of those, 117 have been archived; 12 have reached the judgment stage, and 6 have been transferred to other institutions due to competence issues. None have resulted in disciplinary sanctions.

Necessity for Change

On one hand, repression has been lucrative for arms companies. Regarding former presidents who have used the police as a containment barrier against issues of social inequality, it has not proven useful for them; however, they do not criticize the brute force they deployed. This is a point that the government agenda should address in a debate about police reform: Will social problems continue to be addressed with a militarized police?

On the path to police reform, society expects, at the very least, transparency and accountability from the security forces. The omission of concrete actions in response to the court rulings has created a gap in citizen trust and perpetuated impunity.

However, American academic Alex Vitale, dedicated to the study of police violence, proposes that police brutality is not resolved with better training, diversity in the force, or ‘better’ methods. Instead, he argues that the solution lies in removing the police from all areas of public life where it is not strictly necessary, as their function should not be to solve social problems neither to implement surveillance and control policies against the poor and marginalized.

The goal is to break the vicious cycle of repression, impunity, and arms spending. To achieve this, it is essential to reconsider the scope of the police and address social issues through the reduction of inequality.

This research has been developed with the support of the Human Rights Investigation Lab at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Si encuentras un error, selecciónalo y presiona Shift + Enter o Haz clic aquí. para informarnos.