Lea aquí la versión en castellano [ES] de este reportaje.

Surrounded by coca crops and armed groups that subjugate them, the Awá indigenous people of Tumaco (Nariño) resist the destruction of their culture and territory.

The Awa people have not known peace since the signing of the agreements between the Colombian State and the former FARC-EP guerrillas in November 2016. They have not witnessed the implementation of the agreed-upon substitution of illicit crops. On the contrary, their situation has worsened as armed groups now have a greater presence in their territories and forcibly compel them, at gunpoint, to continue cultivating coca leaves.

Trapped in the murky cocaine business

The National Plan for the Substitution of Illicit Crops (PNIS), defined in the peace agreements, was supposed to achieve within ten years not only the permanent abandonment of coca leaf cultivation as a means of livelihood but also the implementation of alternative economic and social solutions to prevent the people who lived on these crops from falling into the hands of criminal organizations. However, due to poor implementation during the governments of Juan Manuel Santos and Ivan Duque, coupled with the resurgence of the so-called ‘war on drugs’ and the COVID-19 pandemic, the Awa people’s way of life has been profoundly affected, leaving them worse off than before.

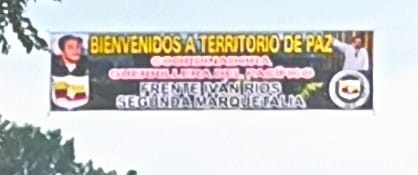

Not only did the cultivated coca plantations expand in the Awa territories in the department of Nariño, located alongside the Colombia-Ecuador border. This is especially serious in the municipality of Tumaco, where the presence of armed groups in indigenous territory has multiplied: Colombian military, Mexican drug trafficking cartels, criminal gangs, paramilitaries and guerrillas operate in the areas where the Awa have lived for many generations. However, it’s the dissident groups of the former FARC-EP that have the most control there today, following the COVID-19 pandemic quarantines. The Front 30 and the Ivan Rios Front have strengthened their position and have undermined roads and schools, confining most of the communities in the Awa reserves of Tumaco to produce increasingly cheaper coca through violence and intimidation, at a time when global demand is increasing due to rising cocaine consumption in Europe and the United States during and after the pandemic.

In its «Global Report on Cocaine 2023,» the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) states:

«In 2020, coinciding with theonset of Covid-19, the number of deaths attributed to cocaine use disorders spiked abruptly, rising by 36 per cent over the level in 2019, the largest year-on-year change (in relative terms) since 2010. Based on preliminary data, the increased levels were sustained into 2021.»

The situation is dire: in 2009, the Constitutional Court declared that the Awa people were at risk of extermination due to displacement and violent death of their members. Today, this situation has worsened due to intense mining activities, confinement, the assassination of leaders, and the recruitment of their young members.

According to reports from the Indigenous Unity of the Awa People (UNIPA), the largest organization of this ethnicity in Nariño, from January 2022 to March 2023, 26 Awa indigenous people have been killed, averaging nearly two deaths per month. There have been 11 mass displacements and nine instances of confinement, affecting 10,743 individuals from the Awa people in Colombia within a year, nearly half of their population.

Armed presence in Awa communities

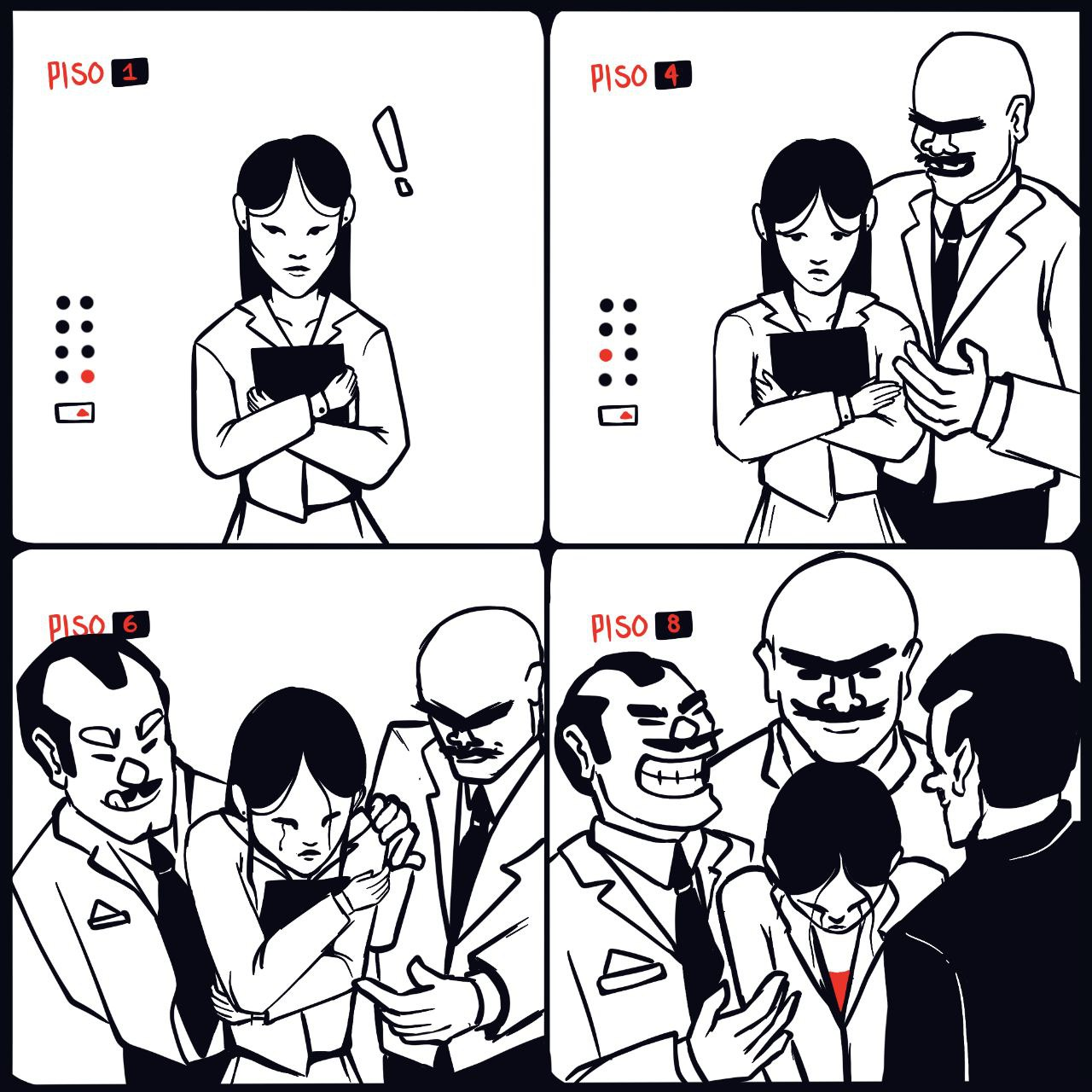

This situation has been exacerbated by the imposition of coexistence on the indigenous people by armed actors. Since 2016, when the peace agreements were approaching, and the emergence of dissident groups was starting to be discussed, various guerrilla factions began to establish a presence in Awa villages, something that had never been seen in the Pacific region of Nariño during the former FARC-EP’s time. Mario*, an indigenous leader, recalls:

«Armed actors never used to occupy communities or settlements; before 2016, armed actors lived in the forest. They moved around, yes, but now the armed actors of this time occupy indigenous people’s homes, they occupy settlements, they occupy villages, and it is more evident that they are involved with the drug trade. So, that is the dispute they have, in the territories where there is more coca, they fight over it […] They want to dominate the territory where there is coca because there is money there.»

The situation worsened with the pandemic. In an area where the presence of the State has been limited to the militarization of territories, and where communities have not even been allowed basic infrastructure, roads, or public services, the sanitary quarantines and the population’s needs facilitated the entry of armed groups who not only carried guns but also offered practical solutions. For example, during that time, the Front 30 arrived at the Chinguirito Mira Awa reserve in Tumaco with heavy construction machinery that was used to repair local roads that the indigenous people badly needed. These situations have been exploited by the dissidents to co-opt indigenous authorities and individuals from the Awa people throughout the region.

According to Blanca*, another Awa leader, offers to indigenous governors were common, especially from alias ‘Robledo’, the Front 30 commander, who, in her words, asked them: «What do you need us to do? A health center, a school? What do you want?»

Similarly, Dario*, another Awa leader, states that with the armed groups’ presence in indigenous communities:

«The armed actors began to organize with more strength; they began to recruit minors, children, and adults. Also, due to the pandemic and the emerging needs […] despite our efforts to strengthen traditional medicine and food supply […] we oversight security. So, the armed actors gained strength; they entered the communities with persuasive strategies and gained power.»

However, it has not been only through persuasion that the armed groups have solidified their power in Awa communities. Gradually, they imposed restrictions on the indigenous people’s movement within their territory, which intensified during the pandemic. They even imposed death as a punishment for those who disobeyed their orders. Dario asserts that:

«When communities leave their areas to buy products from outside, the armed groups see it as a threat, as if they are passing information [to rival groups]. So, when a family leaves, they are murdered on the way to the main road that leads from Pasto to Tumaco […] The control over the communities is intolerant […] they have instilled terror within the collective territories; they have been killing many civilians, including indigenous leaders, indigenous guards, [indigenous] governors, former governors, and there have been many mass displacements, as well as small-scale displacements and confinement […] we could say that most of the Tumaco municipality’s reserves are currently under confinement.»

Unable to leave their settlements or move freely through their territories, the Awa people have been at the mercy of armed organizations that have increasingly imposed rules of behavior on them through fear. Mercedes*, another Awá leader, states:

«No community is free to walk around as before, as armed actors are present in all territories. Since they have their representatives here […] one feels watched and unable to do anything. In my case, I do feel very limited and without freedom, unable to think freely and unable to do many things we should be doing in our communities.»

This situation has only worsened over time. On February 1, 2023, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) issued a humanitarian alert due to the mass displacement and confinement of 676 people from the Awa communities of Piedra Sellada and Sangulpi Palmar, resulting from armed conflicts and the presence of landmines. The same document indicates that in January 2023, three Awa indigenous people were affected by these devices, with one being killed, and two others wounded.

In addition to this, there have been attacks on their leaders, who are now being targeted. This was evident in the attempted assassination of Floriberto Canticus Bisbicus, the Secretary-General of UNIPA, an organization that represents 32 Awa reserves, which occurred on March 7, 2023.

Confinement and dispossession

Impositions by armed groups against the Awa people have gone far beyond, especially in the areas controlled by the Ivan Rios Front. Mario summarizes this situation:

«They came [unknown individuals] there to say ‘sell me.’ If [someone] doesn’t sell, they kill him and take the land for themselves. But if he sells, they also kill him to recover the money they gave to the coca grower, then they wait for him on the road, kill him, and take the money.»

According to Mario’s testimony, many murders follow this pattern, and he recalls a particular case: that of Laurencio Pai, the eldest son of his family, who took care of his parents by cultivating coca on his two-hectare land. Mario claims that after the pandemic, men from the Ivan Rios Front demanded that Laurencio sell his land under the threat of death:

«He told me: ‘I sold my land, they forced me to sell, they gave me COP 100 million, and now, last Saturday when I was in Llorente, they came to ask me for the money. What do you think they’re going to do to me?’ […] This was three days before the murder […] He went to Llorente again, went to a public establishment, and they grabbed him, put him on a motorcycle, and took him away. They called us and told us: ‘Look, they took Laurencio.’ We knew who they were because people know who the armed actors are […] We started the search, and after three days, we found the place where they killed him. They killed him with knives, about 78 stabs.»

These crimes against the Awa people are compounded by extortion. The NGO Indepaz cites in its report «Economies of Armed Conflicts in Colombia: Approach to the Narcotrafficking Value Chain» that in 2022 there were 6,854 reported cases of extortion in the country, a 17% increase compared to 2021. In Nariño department alone, 151 cases were reported, with 29% of them occurring in Tumaco. The NGO’s data comes from the Observatory of Human Rights and National Defense of the Ministry of Defense.

The assassination of Juan Orlando Moriano

The current humanitarian situation for the Awa is unprecedented, but nothing has been as destructive to them as the killings of their leaders. On July 3, 2022, armed groups went so far as to kill Juan Orlando Moriano, one of the most recognized leaders of the Awa people, who had been the coordinator of the indigenous guard and was the deputy governor of the Inda Sabaleta reserve at that time. John Faver Nastacuas and Carlos Jose Garcia, both differential focus guards dedicated to protecting indigenous leaders, also fell alongside him.

The day before, an indigenous guard was killed in the Inda Sabaleta reserve to attract Juan Orlando, according to Dario. When Moriano, an indigenous authority in the area, arrived at the location with other leaders, an ambush occurred:

«They had it all planned […] There were about 300 or 400 meters of dirt road. We went there, and we saw the armed actors cordoning off the road: on one side, there were motorcycles, and on the other side, there were cars, and they narrowed the road. There was no way to move. They were in the middle, more than 15 men, and that’s when it happened, they killed the deputy governor […] We had a tough fight with them: sticks against firearms, and there were five wounded […] Then, as a permanent assembly was declared, the other reserves joined. That lasted more than a month […] The U.S. embassy was there, international human rights commissions were there during the minga, and the minga continues.»

Juan Orlando was 35 years old, and it was very likely that he would have become the governor of his reserve in the near future. He opposed, as the UNIPA had, the presence of coca crops in their territories. He always stated that the path was peace, not war, and that these crops were part of the war. His assassination deeply affected the Awa people and would have been committed with the intention of reducing autonomy for the indigenous and maintaining control of the armed groups over the Inda Sabaleta reserve. The communities point to the Ivan Rios Front as responsible for these crimes.

However, the admiration that Juan Orlando Moriano generated among other Awa people, especially among indigenous guards and youth, led to strong rejection of the crime. According to Mario, «they thought that with the fall of the deputy governor, they would dominate the territory […] It has been very difficult for them […] During the permanent assembly, there were more than 1,500 or 2,000 indigenous people.»

Controlled by coca

This situation also occurs in other reserves. Mercedes indicates:

«We have identified that they are at the service of narcotrafficking […] They fight for territorial control in Inda Sabaleta, in the reserves that have more coca, as well as in Chinguirito Mira, where almost 100% of the territory has coca. So, there is a lot of money, and they don’t want to share it among themselves; one of the two wants to handle it directly […] They also fight for the drug trafficking routes. There are strategic routes on both sides: on the side of the Rosario River, where it connects with Cauca, and on the Mira River, which is the border area and connects with Ecuador.»

In 2016, the community of the Chinguirito Mira reserve, located in the jungle on the border between Colombia and Ecuador, began to build a road to transport their products to the town of Puerto Rico in Mataje, in the neighboring country. However, after the peace agreement, the road became a source of danger for the lives of the Awa. Mercedes explains:

«It’s a strategic river site and also in the jungle. When it’s a nice day and not too muddy, it’s possible to travel. That has facilitated people passing through and has weakened the self-government […] because of the threats and intimidations. The leaders have also suffered. This people start saying, ‘I’ll give you so much money for you to buy,’ or they start sweetening them up. That has made some leaders start looking at that part with interest, and that’s how they lure them. Before they know it, they say, ‘you’re working with the other group,’ and they start seeing them as military targets.»

The profitable coca business has not only brought the expansion of coca crops and widespread fear due to the presence of armed actors to the Awa, but it has also attracted people from other areas of the country seeking a living among the coca fields.

Settlers have arrived at the Chinguirito Mira reserve to make a living by cultivating coca or processing coca paste in small laboratories. Many have settled on lands that were excluded from the reserve, which has affected the persistence of the crops and the process of cultural extermination. Blanca recounts:

«We are surrounded by coca: more than 180 hectares, if I am not mistaken, were excluded from the titling of the territory, so, in these areas, the settlers have come, people from Caqueta, from Meta […] That has also harmed us: when some people arrive and take over the excluded lands, people from outside bring workers, arrive with the purpose of harvesting, and scraping.»

A cocaine-saturated war

The factors that led to this serious situation for the Awa people can be found in how the Colombian state addressed two key issues in the Pacific region that were meant to be resolved through the peace agreement: the reintegration of former guerrillas into civilian life and the substitution of illicit crops. Both areas experienced significant failures that rendered the proposed solutions unviable and further degraded the war in this part of Colombia.

Towards the end of the last century, with the implementation of Plan Colombia and the aerial spraying of herbicides on areas where coca plantations were believed to be located, these crops started moving from Putumayo and Caqueta Departments towards the jungles in the west of Nariño, especially in the municipality of Tumaco. Gradually, this activity expanded into indigenous and Afro-descendant territories since coca paste production had become the best option to increase the meager incomes of the poor population in this region. During those years, the guerrillas regulated the prices and trade of the alkaloid, turning the business into a safe and stable livelihood for producers and buyers.

By 2016, Tumaco had become the area with the highest production of coca leaf, coca paste, and cocaine hydrochloride in Colombia, and an emerald green color dominated the view in large patches visible amidst the jungle: plantations multiplied as the Mira and Rosario rivers served as corridors to transport the alkaloid to the Pacific Ocean and send it to international markets, with a small percentage being sold in villages such as Llorente, La Espriella, and La Guayacana.

The peace agreement signed in 2016 failed to interfere with the lucrative business, and multiple armed groups emerged even before the former FARC-EP guerrillas laid down their weapons, such as La Gente del Orden and later, the dissidents of the Guerrillas Unidas del Pacífico and the Oliver Sinisterra Front, as well as the «Contadores,» who served as mercenaries for paramilitaries and drug traffickers, among many others. Two years after the peace agreement, at least 14 criminal structures were present in Tumaco, competing for control over coca economies and other illicit revenues as part of their war strategies.

These issues were compounded by the failures in implementing the peace agreement. When Henry Castellanos, known as ‘Romaña’ in the guerrilla, coordinated the Veredal Zone of Transition and Normalization (ZVTN) of La Variante in Tumaco, where former guerrillas gathered to lay down their arms, he did not accept more than 500 militiamen from Tumaco and expelled «73 youths who had contacts with Mexican drug traffickers and the Clan del Golfo, among whom was Walter Patricio Arizala, alias ‘Guacho’,» as reported by Insight Crime.

The problems continued with the arrival of the Frente 29 and the Columna Movil Daniel Aldana to La Variante on January 30, 2017. The company contracted by the Santos government to carry out the infrastructure works only provided 4 portable bathrooms and a cleared and flattened land that was uninhabitable. The works never progressed beyond 70% completion, and despite efforts to keep the process of reintegration of ex-combatants going, the situation worsened with the presence of dissidents and new armed groups.

In 2018, ‘Romaña’ fled Tumaco for Meta when the reintegration project faced two situations that put the security of ex-combatants in La Variante at risk: the capture of Aldemar ‘Tito’ Ruano by the Police on October 20, 2017, inside the then Ariel Aldana Territorial Space for Eduaction and Reincorporation, and subsequent threats from alias ‘Guacho’, the same young man he had expelled from there, who was by then the commander of the most powerful dissident group in the region, the Oliver Sinisterra Front.

Since then, fear and mistrust, combined with a clear lack of action from the State, led many ex-combatants to leave the area, and by 2019, only 75 Ex-FARC members and around 200 of their relatives remained in La Variante. It was evident the lack of political will from the government to provide security for those who signed the peace agreement or to ensure that the funds allocated for reintegration were used appropriately.

Over time, the intense armed confrontation and the militarization of the territory as the State’s only response led several of the armed groups that emerged during that time to disappear, while others unified or were absorbed by larger ones.

Today, in Tumaco, the two largest dissident groups from the former FARC-EP dominate: on one side, the Frente 21 ‘Ivan Rios’, linked to the Central High Command commanded by Nestor Gregorio Vera Fernández, known as ‘Ivan Mordisco’, and which incorporated former members of the Guerrillas Unidas del Pacífico and the Contadores, controlling the Rosario River; and, on the other side, the Frente 30, which recently joined the Western Bloc ‘Alfonso Cano’ of the Segunda Marquetalia led by Luciano Marín Arango, better known as ‘Ivan Marquez’.

Substitution: failures and tragic consequences

The other major problem was the failures of the National Program of Substitution Initiatives (PNIS). In the Nariño Pacific region, the state entities responsible for the program exposed the identity of people who joined the initiative, resulting in threats, extortion, displacement, and even killings by armed groups targeting those who wanted to abandon the coca economy. Meanwhile, the Police continued forced eradication of crops with an ‘escalation’ strategy, which was supposed to avoid affecting those who were about to begin their voluntary substitution process, but payments to the farmers did not arrive, leading to increased conflict over coca, poverty, and fear.

As Mario recalls:

«Some received two payments, others received one payment, and so on […] Apart from that, what came was killings because when the PNIS program started, the government said: ‘we must sit down to sign the intention form’, and they sat down with the ministry responsible for the social and community leaders to sign the intention form […] The first thing the government did was to publish that list, with specific names, because we reviewed the list […] There the armed actors did their thing and started killing many leaders of community councils. But another retaliation also came from the same government: they took advantage of the signatures and […] they implemented forced eradication.»

In the context of forced eradication, on October 5, 2017, the first massacre after the signing of the peace agreement occurred on Awá territory: the Tandil massacre. The security forces fired on civilians during manual coca eradication carried out in the Awa reserve of Piedra Sellada. As Dario, an Awa leader who faced the situation, recounts:

«The Police were the ones who carried out the massacre. This massacre occurred in the collective territory of the Awa people UNIPA, which was Piedra Sellada, and nearby was a community called Tandil […] Two Awa indigenous people and two indigenous people from Cauca were also killed there, as well as several protesters from the coca farmers; it was a pretty big massacre.»

Although the Prosecutor’s Office charged Captain Javier Enrique Soto Garcia, commander of the Delta Nucleus of the National Police, and Major Luis Fernando Gonzalez Ramirez, commander of the Dinamarca Platoon of the National Army, with aggravated homicide and attempted homicide in the context of the massacre, trust in the PNIS and peace was shaken in Tumaco. Over time, the substitution program dwindled without changing the situation for coca growers as promised.

Santos failed to implement peace policies in Tumaco, and when Duque came to power, he exacerbated the situation by further militarizing the territories. In the five years between the signing of the agreement and Gustavo Petro’s presidency, the State did not guarantee the security of ex-combatants or the Awa people, nor did it offer alternatives to coca growers other than waging war and keeping their communities in poverty.

In 2021, according to a report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the Integrated System for Monitoring Illicit Crops (SIMCI), coca crops increased from 50,701 hectares to 89,266 hectares in Colombia, with Tumaco being the municipality with the largest coca area, covering 9,276 hectares.

A lucrative market

Today, the situation for small coca producers in Tumaco remains complex. Before the pandemic, an Awa indigenous person sold two kilograms of coca paste for 1,500 USD every three months, with a profit margin of 50%, meaning they had 750 USD for their expenses. Today, they are paid 420 USD per kilogram, barely earning between 50 and 125 USD. On the other hand, drug traffickers need at least 10 kilograms of coca paste to refine one kilogram of cocaine hydrochloride, which can be smuggled to Europe or the United States, where the drug’s price remains steady at USD 100 or EUR 100 for 0.8 grams of the alkaloid on the streets.

Blanca shares her experience:

«Well, right now, I heard from people that it’s decreasing a lot: sometimes they pay 1,000, 1,600, 1,700 [pesos per gram of coca paste], and that’s very little; 3,000, well, that’s a profit […] in [Inda] Sabaleta, they said they had money, but they were selling to whomever they [the armed groups] wanted. Those who know how to process […] they are now paying around 1,600 pesos per gram, and they can’t sell to just anyone but to those who the mafia sets for them, and they can set any price they want.»

Additionally, armed groups and the drug trafficking economy have also taken over all the gasoline that enters or is produced illegally in Tumaco. People complain at gas stations in Llorente, La Espriella, and La Guayacana because gasoline runs out quickly, leaving car and motorcycle owners without fuel. This happens because owners of coca cocaine processing labs pay people to bring 20-gallon containers, or ‘pomas,’ from the gas stations to the laboratories in the forest.

On the other hand, the dissidents control the gasoline that is handmade from the oil stolen from the Transandean Pipeline, which runs parallel to the Mira River and carries the oil to the port of Tumaco, where tankers are filled for transportation around the world. All this illegal fuel is destined for the processing of the alkaloid, which is also taken to the Pacific for passage to international markets.

Blanca says:

«There is no gasoline […] there they fill the ‘pomas’, and it runs out quickly […] they also buy [gasoline] pirated. I know that in Sabaleta, they arrived at the cemetery with the pirated one, the one they extract from crude oil […] So, those are the strategies they have always had, and they depend on the fronts, depending on what they extract and compile in their labs.

The social and environmental damage to the lives of the Awá people and their ecosystem is incalculable. Since 2007, the oil pipeline has been perforated to extract crude oil and take it to pools where it is refined into artisanal gasoline. Leaks and spills occur daily, contaminating both the jungle soils and several rivers that flow into the Pacific Ocean. This has particularly affected the Awa reserves of Gran Sábalo, Gran Rosario, Nunalbi, and Sangulpi.

The State’s response to the environmental problems this generates is not promising either. Cenit, a subsidiary of the state-owned oil company Ecopetrol responsible for oil transportation and the pipeline, washes its hands, arguing that this is a matter of public security, and evades its responsibilities in mitigating environmental impacts. Meanwhile, the Army’s practice of setting fire to oil spills or artisanal gasoline refining pools in the middle of the jungle exacerbates the damage. Blanca describes it like this:

«The Army doesn’t have safety protocols and burns [the spills]. The smoke rises, and the ashes fall […] Sometimes the people who are sowing, whether it’s tomatoes, cucumbers, corn, or plantains, that also kills them […] You have your tomatoes here, and the ashes fall, and the plant dies due to the chemicals. The water we collect from the rain also turns black.»

Total peace?

Today, the Awa people have expectations regarding the new government’s policy of total peace under Gustavo Petro’s leadership. They know that dialogue is the path to stop the violence in their territory. During these first months, the first left-wing president in Colombia’s recent history has shifted the focus from persecuting producers to once again focusing on voluntary substitution programs, raising hopes among the Awa.

On April 20, the new Colombian president announced, together with U.S. President Biden, a commitment from both states to reduce demand and «expand bilateral cooperation in intelligence and interdiction to dismantle networks, pursue the true owners and facilitators of this business in their jurisdictions, and target illicit finances.» This would signify a political shift towards the end of the so-called ‘war on drugs’, which has been fixated on repressing producers, often the poorest, and has had serious consequences for indigenous communities.

It is hoped that Europe and the United States will take responsibility for the failure of the ‘war on drugs’ in their countries and address the problematic drug consumption of their citizens, which drives the incessant demand for the alkaloid, an addiction that ultimately finances the slow extermination of the Awa people.

However, it is also necessary to address the lack of political will to implement the peace agreements by the Santos and Duque governments: their decisions continue to cost lives to the Awa indigenous people, the last guardians of this corner of the Choco biogeographic jungle, one of the largest buffers against climate change in the world.

This investigation received support from International Media Support for the initial stage of the investigation.

Si encuentras un error, selecciónalo y presiona Shift + Enter o Haz clic aquí. para informarnos.